Raijū

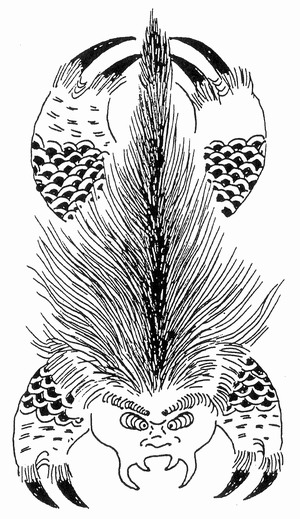

In Japanese mythology, the raijū (雷獣, らいじゅう; literally "thunder animal" or "thunder beast") is a legendary creature intimately associated with lightning and thunder phenomena, as well as with Raijin, the Shinto god of lightning and storms. The raijū represents one of numerous Japanese yōkai (supernatural creatures) that personify natural forces and serve to explain meteorological phenomena that pre-modern people found mysterious and terrifying.

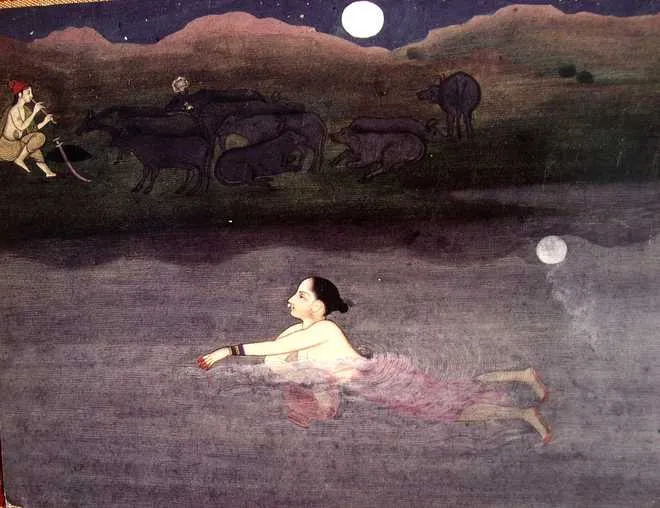

A raijū's body is fundamentally composed of or wrapped in crackling lightning energy, making it a living embodiment of electrical discharge. The creature is most commonly conceived as taking the form of a white-blue wolf or dog wreathed in lightning, though Japanese folklore attributes remarkable shape-shifting abilities to the raijū, allowing it to manifest in an extraordinarily wide variety of animal forms. These alternative forms documented across different regional traditions and historical accounts include: tanuki (Japanese raccoon dog), rabbit, porcupine, bear, squirrel, rat, mouse, deer, boar, leopard, fox, weasel, black or white panther, serow (Japanese mountain goat-antelope), ferret, marten, various marine mammals (including whales, dolphins, and seals—suggesting raijū can inhabit both terrestrial and aquatic environments), tiger, and cat. This remarkable morphological flexibility reflects how different communities interpreted lightning phenomena through their local fauna and how the legend adapted across Japan's diverse geographical regions. The raijū may also manifest as a pure ball of lightning flying through the air without any animal form whatsoever, and indeed, some scholars suggest the entire raijū legend may represent pre-scientific attempts to explain mysterious lightning phenomena including ball lightning, those rare, poorly understood luminous spheres that occasionally appear during thunderstorms and drift through the air before dissipating or exploding. The creature's cry is said to sound exactly like thunder, creating an auditory manifestation of storm phenomena that complements its visual lightning form.

The raijū serves as the companion, attendant, or pet of Raijin, the Shinto god of lightning, thunder, and storms, who is typically depicted as a fearsome demonic figure surrounded by drums that he beats to create thunder. While the raijū beast is generally described as calm, docile, and harmless during fair weather—essentially a peaceful creature that poses no threat to humans or property when storms are absent—its behavior transforms dramatically during thunderstorms when it becomes intensely agitated, excited, and frenzied by the electrical energy filling the atmosphere. In this agitated state, the raijū leaps frantically about in trees, across fields, and even onto and through buildings, jumping from place to place with supernatural speed and energy. Trees that have been struck by lightning and show characteristic damage—scorched bark, split trunks, and torn wood—are said in Japanese folklore to have been scratched and clawed by the raijū's talons during its storm-driven frenzy, providing a folkloric explanation for lightning damage that attributed destructive natural phenomena to the actions of a supernatural creature rather than to impersonal electrical discharge.

One of the raijū's most peculiar and distinctively Japanese folkloric behaviors involves its supposed habit of sleeping in human navels. According to this tradition, when a raijū takes shelter and falls asleep curled up inside a person's navel (presumably while in a small animal form rather than its larger manifestations), this creates a dangerous situation: Raijin, seeking his missing companion or attempting to wake the sleeping raijū, shoots lightning arrows or bolts down from the sky aimed at the creature to rouse it from slumber. However, because the raijū is nestled inside a human's navel, these lightning strikes inevitably harm or kill the unfortunate person in whose belly the demon is resting, making them collateral victims of Raijin's attempts to retrieve his wayward pet. This belief created practical behavioral consequences: superstitious people in Japan traditionally slept on their stomachs rather than on their backs during bad weather and thunderstorms, protecting their navels from becoming raijū shelters by keeping them pressed against sleeping mats or futons. However, other regional variations of the legend claim that raijū only hide in the navels of people who sleep outdoors exposed to the storm rather than safely sheltered indoors, suggesting that the superstition also functioned as encouragement to seek proper shelter during dangerous weather rather than sleeping in fields or forests where lightning strikes were more likely.

Scholars researching the origins and development of raijū mythology believe that the myth likely originated from or was significantly influenced by the Chinese materia medica text Bencao Gangmu (Compendium of Materia Medica), a comprehensive pharmaceutical and natural history encyclopedia compiled by Li Shizhen during the Ming Dynasty, which described various creatures and natural phenomena and which was known and studied in Japan. Historical researchers have found evidence suggesting there were reported raijū sightings and formal documentation of supposed encounters with these creatures during the Edo period (1603-1868) in Japanese history, when such supernatural explanations for natural phenomena remained culturally accepted and when mysterious events were routinely attributed to yōkai and other supernatural causes. However, scholars also recognize that these "sightings" and the raijū legend's prominence during this period reflect the state of scientific understanding at the time: because the sky and upper atmosphere remained completely unexplored territories beyond human access or investigation, and because Western scientific and technological knowledge regarding meteorology, atmospheric electricity, and lightning phenomena had not yet been transmitted to or adopted in Japan during the Edo period, the mysterious, dramatic, and dangerous phenomena of thunder and lightning were naturally attributed to supernatural causes, specifically to the malevolent or mischievous notoriety of raijū rather than understood as natural electrical discharges resulting from atmospheric conditions.

The raijū acquired predominantly negative connotations in Japanese folklore and popular consciousness because many frightening and incomprehensible things were happening in the sky—thunder, lightning, storms, meteors, and other atmospheric phenomena—that remained completely beyond the reach of human understanding, control, or investigation during the Edo period. This negative characterization becomes more understandable when contrasted with attitudes toward the ocean: while the depths of the seas were equally inaccessible to human reason and exploration during this period and contained their own mysteries and dangers, oceans simultaneously provided tangible, daily benefits to Japanese coastal and island communities by supplying abundant fish for food, enabling transportation and trade, and sustaining countless life forms that humans could observe and utilize. The ocean, despite its dangers and mysteries, was fundamentally life-giving and economically beneficial. In this sense, celestial phenomena represented by the raijū were transcendental, remote, purely dangerous without offsetting benefits, and incomprehensible in ways that inspired fear and negative associations, whereas oceanic phenomena, though equally mysterious in many respects, were integrated into daily life and survival in ways that created more balanced or even positive connotations. The raijū thus embodies pre-modern Japan's anxious relationship with atmospheric phenomena that could strike without warning, kill without explanation, and remained forever beyond human reach or comprehension until scientific meteorology provided natural rather than supernatural explanations for thunder, lightning, and storms.