Marco Polo

Marco Polo (Venetian: [ˈmaɾko ˈpolo]; Italian: [ˈmarko ˈpɔːlo]), born approximately 1254 and deceased January 8, 1324, was a Venetian merchant, explorer, and writer whose extraordinary journey through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295, and the subsequent account of his experiences, fundamentally transformed European understanding of the Eastern world and catalyzed centuries of Western engagement with Asia. His travels are documented in The Travels of Marco Polo (also known as Book of the Marvels of the World and Il Milione, composed around 1300), a work that described the then-mysterious culture and internal organization of the Eastern world, including the immense wealth and territorial expanse of the Mongol Empire and China under the Yuan dynasty. This narrative provided Europeans with their first comprehensive and detailed examination of China, Persia, India, Japan, and other Asian societies, introducing Western readers to civilizations whose sophistication and scale challenged European assumptions about their own cultural superiority and geographic centrality.

Born in Venice, Marco learned the principles and practices of mercantile trade from his father Niccolò and his uncle Maffeo, who had themselves traveled through Asia and secured an audience with Kublai Khan, the Mongol ruler of China and grandson of Genghis Khan. In 1269, the two brothers returned to Venice, where Marco met his father for the first time—Niccolò having departed on his Asian journey before Marco's birth or during his early childhood. The three Polos embarked together on an epic journey to Asia, exploring numerous locations along the Silk Road—the ancient network of trade routes connecting Europe and Asia—until they reached "Cathay," the medieval European term for northern China.

They were received by the royal court of Kublai Khan, who reportedly found himself impressed by Marco's intelligence, linguistic aptitude, and deferential humility. Recognizing the young Venetian's talents and potential usefulness, Kublai appointed Marco to serve as his foreign emissary, entrusting him with diplomatic missions throughout the vast Mongol Empire and Southeast Asia. In this capacity, Marco visited territories that correspond to present-day Myanmar, India, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam, observing diverse cultures, political systems, and economic practices across an enormous geographic range.

As part of his extended service to Kublai Khan, Marco also traveled extensively throughout China itself, residing within the emperor's domains for seventeen years and witnessing countless phenomena, technologies, customs, and natural wonders previously unknown to Europeans. This prolonged residence gave him an exceptionally deep familiarity with Chinese civilization that no other European of his era could claim. Around 1291, after nearly two decades in the Khan's service, the Polos received permission to depart when they offered to escort the Mongol princess Kököchin to Persia, where she was destined to marry a Mongol ruler.

The journey to Persia by sea proved lengthy and perilous, but they arrived there around 1293. After fulfilling their obligation by delivering the princess safely to her destination, the Polos traveled overland through Persia to Constantinople and then proceeded to Venice, finally returning to their home city after an absence of twenty-four years. The Venice they returned to was dramatically engaged in conflict, as the city-state was embroiled in war with its maritime rival Genoa, competing for commercial and naval supremacy in the Mediterranean.

Marco joined Venice's war effort against the Genoese, demonstrating his loyalty to his native city despite his long absence. During naval combat, he was captured by Genoese forces and imprisoned. This misfortune, however, proved historically fortunate for posterity.

While confined in a Genoese prison, Marco encountered Rustichello da Pisa, a romance writer who became his cellmate. To pass the time during their imprisonment and perhaps recognizing the extraordinary nature of Marco's experiences, the two men collaborated on composing an account of Marco's Asian travels, with Marco dictating his memories and observations while Rustichello shaped them into a narrative form influenced by the literary conventions of medieval romance literature. Marco was released from captivity in 1299, returning to Venice where he resumed his mercantile career, achieving considerable financial success as a wealthy merchant.

He married and fathered three daughters, living a comfortable domestic life that contrasted dramatically with his earlier adventures. He died in 1324 at approximately seventy years of age and was buried in the church of San Lorenzo in Venice, ending a life that had spanned some of the most transformative decades of medieval history. Though Marco Polo was not the first European to reach China—earlier travelers including Franciscan missionaries and his own father and uncle had preceded him—he was the first to leave a detailed, comprehensive chronicle of his Eastern experiences that circulated widely throughout Europe.

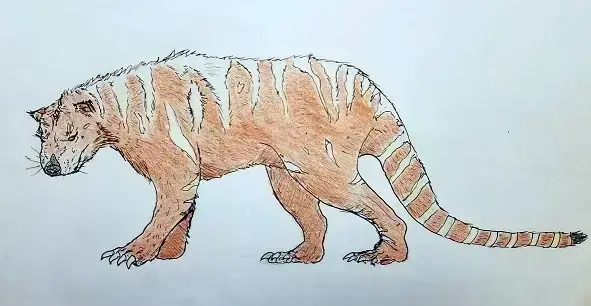

His account provided Europeans with an unprecedentedly clear and extensive picture of Asian geography, political structures, economic systems, and ethnic customs, fundamentally expanding the European geographical imagination. The work included the first substantial Western descriptions of numerous phenomena and substances that would later transform European civilization: porcelain, with its translucent beauty and superior quality compared to European ceramics; gunpowder, which would revolutionize warfare; paper money, a sophisticated financial instrument that astonished Europeans accustomed only to metal coinage; and various Asian plants, spices, and exotic animals previously unknown or known only through fragmentary reports. His descriptions of the vast wealth of Asian kingdoms, the sophisticated administrative systems of the Mongol Empire, and the technological and cultural achievements of Chinese civilization challenged European provincialism and stimulated intense curiosity about the East.

Marco Polo's narrative exercised profound and lasting influence on subsequent European exploration and geographical understanding. His account directly inspired Christopher Columbus, who owned and annotated a copy of The Travels of Marco Polo and was motivated partly by Marco's descriptions of Asian wealth and the Indies when he proposed his westward voyage across the Atlantic, seeking a new route to the riches Marco had described. Numerous other explorers, merchants, and adventurers drew inspiration and practical information from Marco's work, using it as a guide to Eastern geography and a source of motivation for their own journeys.

The substantial literature generated by Polo's writings extended far beyond his original text, spawning translations into numerous European languages, adaptations, commentaries, and derivative works that disseminated his observations throughout medieval and Renaissance Europe. His influence also transformed European cartography in fundamental ways, as mapmakers incorporated his geographical information into their representations of the world. The Catalan Atlas of 1375, one of the most important medieval maps, and the Fra Mauro map of 1450, perhaps the greatest achievement of medieval cartography, both drew extensively on information from Marco Polo's account, using his descriptions to fill in vast territories that had previously been blank or filled with legendary creatures and imaginary kingdoms on European maps.

Through these cartographic works, Marco's observations became embedded in European geographical knowledge, shaping how Europeans visualized the world and understood their place within it for centuries after his death.