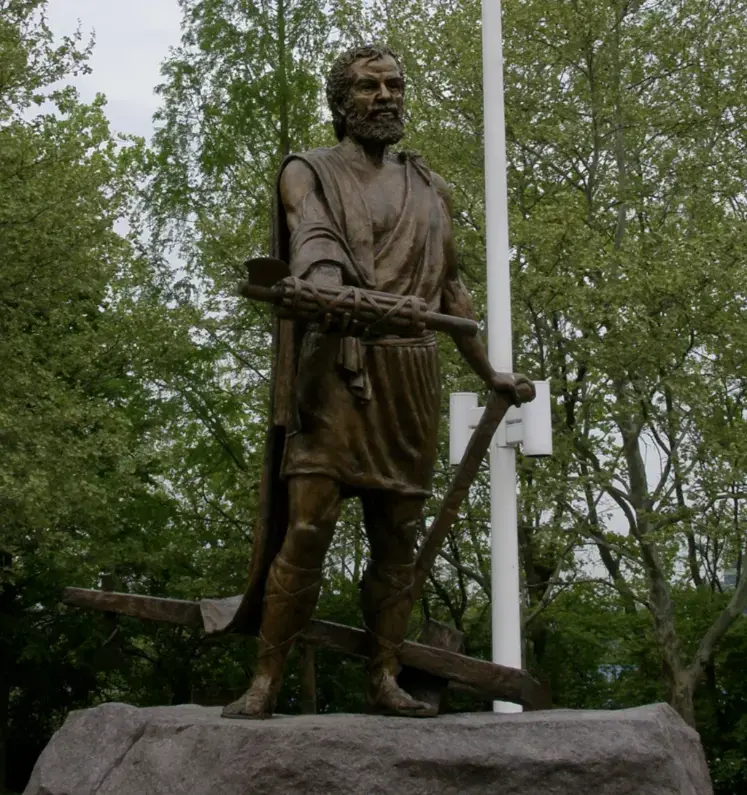

Botond

Botond (also recorded as Bothond or Bontond) was a Hungarian legendary warrior of the 10th century, remembered as a folk hero of the Hungarian invasions of Europe. His most famous feat, told in chronicles, is linked to the Hungarian campaign against the Byzantine Empire in 958 or 959, when he is said to have struck the Golden Gate of Constantinople with his axe, tearing a hole in it, and then defeated a massive Greek warrior in single combat.

The historical Botond is uncertain, for his name and deeds survive only in chronicles written centuries later. The anonymous author of the Gesta Hungarorum (early 13th century) describes him as a tribal chieftain, son of Kölpény, uncle of the Magyar leader Tas, to whom lands were granted during the conquest of the Carpathian Basin. By contrast, Simon of Kéza in his Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum (1280s) portrays him as a common soldier chosen to wrestle the Greek champion, and the 14th-century Illuminated Chronicle follows this version, even quoting Botond’s own declaration that he was “the least of the Hungarians.” This phrase highlights both his humble origin and small stature, which made his triumph all the more impressive.

Scholars remain divided over his background. Zoltán Tóth argued that his family’s later poverty confirms a low social status, and that the name Kölpény may reflect Pecheneg roots, supported by place names in present-day Serbia such as Kulpin and Kupinovo. The etymology of “Botond” has also fueled debate: Dezső Pais linked it to the Turkic verb butan (“to beat, defend”), while others connect it to bot, “rod or mace,” a weapon favored by the Pechenegs.

Some historians instead considered him Magyar, perhaps even a fabricated noble figure invented by Anonymus. Others, like Bálint Hóman and Gyula Moravcsik, accepted the version that placed him among the elite and tied his tribe to lands in Baranya or along the Drava.

Legends describe his exploits in vivid terms. At Constantinople, Botond reportedly struck the metal gates with his axe so hard that a hole was opened wide enough for a child to pass through. Before the watching Hungarians and Byzantines, he then stepped into the arena unarmed, where he wrestled the Greek champion to the ground and broke his arm.

In some versions, the Greek died from his wounds. Botond declared boldly: “I am Botond, a proper Hungarian, the least of the Hungarians. Fetch two more Greeks—one to pray for your soul and the other to bury your body—for surely I shall humble your emperor.”

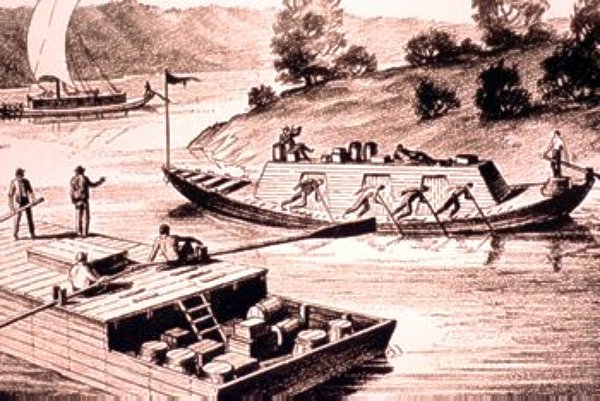

Most scholars connect this tale to the Hungarian raid of 958–959, when Emperor Constantine VII had halted tribute payments. Byzantine sources record that the Hungarians penetrated deep into imperial lands, raiding Bulgaria and reaching as far as Constantinople before retreating under counterattack. The Hungarian chronicles, however, emphasize the duel and the blow against the Golden Gate, which carried symbolic weight: striking the ceremonial gate was a ritual declaration of war, echoing the earlier act of Khan Krum in 813.

The weapon itself, described as an axe or mace, reinforces theories of Botond’s Pecheneg origin.

Later Hungarian chroniclers preserved the legend in varying forms. Elemér Mályusz argued that its focus on wrestling suggests a popular folk origin rather than courtly invention, contrasting a giant Greek with a small, common Hungarian. Henrik Marczali emphasized its survival in oral tradition and its echoes of pagan custom.

Attempts were even made to merge Botond with foreign heroes, such as the Bavarian figure Poto the Brave, but Botond’s story proved too deeply rooted in Hungarian tradition to be replaced. Over time the scene of the duel was emphasized more than the breaking of the gate, reflecting both the evolution of the tale and the gradual Magyarization of the Pechenegs.

By the 13th and 14th centuries, Botond had become a symbol of the Hungarian people themselves: humble yet unyielding, proud defenders of their nation’s honor, and fearless even against empires. His legend endures not simply as the story of one man but as a reflection of the spirit of the early Hungarians.