Arimanius

Arimanius (Greek: Αρειμάνιος, Areimánios; Latin: Arīmanius) is a name for an obscure deity found in a small number of Greek literary texts and five Latin inscriptions, whose identity and theological significance remain subjects of scholarly debate. According to the limited evidence available, Arimanius is portrayed as the opponent or adversarial counterpart of Oromazes (Ancient Greek: Ὡρομάζης, Hōromázēs), identified as the god of light, suggesting a dualistic cosmological framework in which these two deities represent opposing principles or forces. In classical Greek and Roman texts that discuss Zoroastrianism, the Persian religion founded by the prophet Zarathustra, Areimanios (appearing with various spelling variations) fairly clearly refers to the Greeks' and Romans' interpretation and transliteration of the Persian Ahriman (Angra Mainyu), the principle of darkness, destruction, and evil in Zoroastrian theology who opposes Ahura Mazda, the supreme god of light, truth, and goodness.

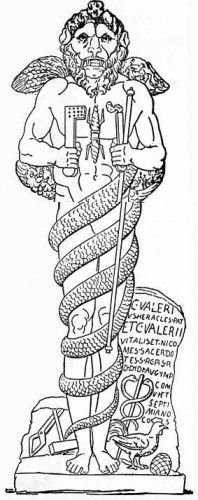

Classical authors attempting to describe Persian religious beliefs for Greek and Roman audiences adapted Persian theological concepts and names into forms comprehensible within Greco-Roman religious frameworks, often simplifying or distorting the original Persian ideas in the process. However, the five Latin inscriptions mentioning Arimanius that have been discovered in explicitly Mithraic contexts—associated with the Mysteries of Mithras, a mystery religion popular in the Roman Empire particularly among soldiers and which incorporated Persian-derived imagery and terminology—suggest that within Roman Mithraism, Arimanius represented a re-defined or substantially different deity from the Persian Ahriman, despite the near-identical name. This indicates that Roman Mithraists may have borrowed the name from Persian tradition but adapted it to serve different theological functions within their own distinct religious system, which, while incorporating Persian elements and aesthetic features, operated according to its own internal logic quite different from actual Zoroastrianism.

The most extended and detailed discussion of Areimanios in classical literature appears in two sections of Plutarch's writings, where the Greek philosopher and biographer describes Areimanios as representing the dark or evil principle in a cosmic dualistic opposition against Oromazes (his rendering of Ohrmazd or Ahura Mazda), the principle of light and goodness. Plutarch presents this dualism as central to Persian religious thought, depicting an eternal cosmic struggle between these two fundamental forces. However, it is crucial to recognize that Plutarch was specifically and explicitly describing Persian Zoroastrianism as he understood it from available sources, attempting to explain authentic Persian religious beliefs to his Greek-reading audience, rather than discussing the mysterious and poorly documented figure of Arimanius as that deity functioned within the Roman Mysteries of Mithras.

In the context of Roman Mithraism—a distinct religion that must be carefully distinguished from Persian Zoroastrianism despite superficial similarities and borrowed terminology—scholarly analysis of how the name Arimanius is actually employed in Mithraic inscriptions and iconography suggests that it seems highly implausible that the figure referred to an evil entity or principle of cosmic evil comparable to the Zoroastrian Ahriman, regardless of how formidable, fierce, or potentially threatening his visual depictions in Mithraic art might superficially appear to modern observers. The Mithraic Arimanius may instead have represented a complex deity serving functions within Mithraic theology and ritual that cannot be simply reduced to "evil opponent," possibly embodying temporal power, material manifestation, necessary opposition within a cosmological system, or other concepts that do not map neatly onto the good-versus-evil dualism that Plutarch described in his account of Persian religion. This divergence between the Persian Ahriman and the Mithraic Arimanius exemplifies the complex processes of religious borrowing, adaptation, and transformation that characterized the multicultural religious landscape of the Roman Empire, where deities, names, and concepts migrated between different religious systems and were refashioned to serve new theological purposes often quite different from their original meanings.