Peter Stumpp

Peter Stumpp (c. 1530–1589; name also spelled Peter Stube, Peter Stubbe, Peter Stübbe, or Peter Stumpf) was a German farmer accused of serial murder, werewolfery, witchcraft, and cannibalism in one of the most sensational and disturbing witch trials of the late sixteenth century. He became known as "the Werewolf of Bedburg" and his case represents one of the most extensively documented werewolf prosecutions in European history, though the reliability of the evidence against him remains deeply questionable given the use of torture to extract confessions.

The most comprehensive source on the case is a sixteen-page pamphlet published in London in 1590, which was an English translation of a German original of which no copies have survived. Two copies of the English pamphlet exist today—one preserved in the British Museum and one in the Lambeth Library—and the document remained largely forgotten until the occultist Montague Summers rediscovered it in 1920. The pamphlet provides a detailed account of Stumpp's life, his alleged crimes, and the trial proceedings, and includes numerous statements purportedly from neighbors and witnesses regarding the crimes.

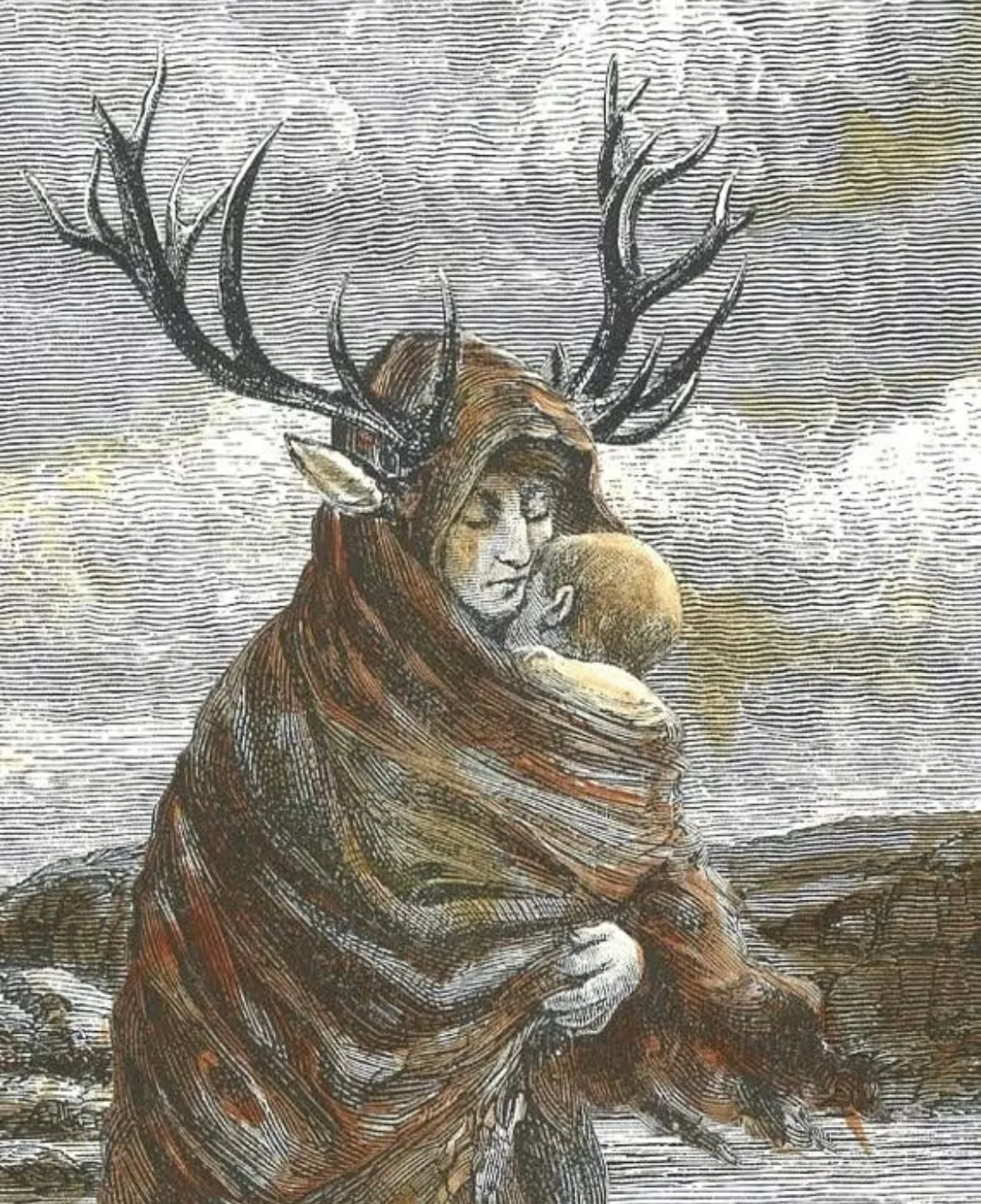

Summers reproduced the entire pamphlet, including its accompanying woodcut illustration, on pages 253 to 259 of his 1933 work The Werewolf, making this rare document accessible to modern readers and researchers. Additional contemporary information about the case is provided by the diaries of Hermann von Weinsberg, an alderman from Cologne who recorded notable events of his time, and by several illustrated broadsheets that were printed and circulated in southern Germany, reflecting the widespread public fascination with this lurid case. The pamphlet's existence and content were also referenced by Edward Fairfax in his firsthand account written in 1621 describing the alleged witch persecution of his own daughters, demonstrating that the Stumpp case remained known and was cited as precedent in subsequent witchcraft accusations decades after the trial.

Although the exact place and date of Peter Stumpp's birth are unknown, examination of available sources suggests he was likely born near Bedburg, Germany, around 1530. His name appears in various spellings in different documents—Peter Stube, Peter Stub, Peter Stubbe, Peter Stübbe, or Peter Stumpf—and he was also associated with aliases including Abal Griswold, Abil Griswold, and Ubel Griswold, though the origins and significance of these alternative names remain unclear. The surname "Stump" or "Stumpf" (meaning "stump" in German) may have been given to him, or may have taken on additional significance, because his left hand had been cut off at some point, leaving only a stump.

According to the accusations against him, this mutilation was cited as proof of his guilt: witnesses claimed that the werewolf they had encountered had its left forepaw cut off during a confrontation, and when Stumpp was found to have a corresponding injury—missing his left hand—this was presented as conclusive evidence that he was the werewolf in question, reflecting the peculiar logic of werewolf belief that injuries sustained in wolf form would appear on the human body. Stumpp, who was likely Protestant in an era of intense religious conflict and suspicion, was reportedly a wealthy and respected farmer in his rural community rather than a marginal or impoverished figure, which makes his prosecution somewhat unusual since many witch-hunt victims were poor, elderly, or socially vulnerable. During the 1580s, he appears to have been a widower raising two children: a daughter named Beele (also called Sybil), who was older than fifteen years, and a son whose age is not recorded in surviving sources.

During 1589, Stumpp endured one of the most lurid, sensational, and extensively publicized werewolf trials in European history. After being stretched on the rack—a torture device that pulled the body in opposite directions, causing excruciating pain and often permanent injury—and before additional torture could be applied, he confessed to having practiced black magic and witchcraft since he was twelve years old. According to his confession, which must be understood as extracted under torture and threat of continued torture, the Devil had given him a magical belt or girdle that enabled him to metamorphose into "the likeness of a greedy, devouring wolf, strong and mighty, with eyes great and large, which in the night sparkled like fire, a mouth great and wide, with most sharp and cruel teeth, a huge body, and mighty paws." Stumpp claimed that removing this enchanted belt would cause him to transform back into his human form.

After his capture, he told the local magistrate that he had left this magical girdle hidden "in a certain valley." The magistrate dispatched men to search for and retrieve this crucial piece of evidence, but no such belt was ever found—an inconvenient fact that apparently did not undermine the prosecution's case or cast doubt on the confession's veracity in the minds of the authorities. Over the course of twenty-five years, Stumpp allegedly had been an "insatiable bloodsucker" who gorged on the flesh of domestic animals including goats, lambs, and sheep, as well as on the flesh of women and children. Under the threat of continued and escalating torture, he confessed to killing and cannibalizing fourteen children and two pregnant women, whose fetuses he claimed to have ripped from their wombs and consumed, saying he "ate their hearts panting hot and raw"—flesh which he later supposedly described as "dainty morsels," a detail that seems calculated to maximize the horror and disgust of readers.

Among the fourteen children he allegedly murdered and devoured was his own son, whose brain he reportedly consumed. The confession stated that Stumpp loved his son dearly, but that in the end, his supernatural bloodlust and demonic compulsion overwhelmed his paternal affection. According to the account, Stumpp took his son into the woods, transformed into the likeness of a wolf through the power of his magical belt, and devoured the boy.

Beyond accusations of serial murder and cannibalism, Stumpp was also charged with having maintained an incestuous sexual relationship with his daughter Beele, who was consequently sentenced to die alongside him, and with having engaged in sexual relations with a distant female relative, which contemporary law also classified as incest given the prohibition against sexual relations within certain degrees of kinship. Additionally, his confession included the claim that he had engaged in sexual intercourse with a succubus—a female demon sent to him by the Devil specifically for this purpose—adding a layer of diabolical sexual transgression to the already overwhelming catalogue of crimes. The execution of Peter Stumpp on October 31, 1589, alongside his daughter Beele and his mistress Katherine Trompin, ranks among the most brutal and elaborately cruel executions recorded in European judicial history.

Stumpp was bound to a breaking wheel—a large wooden wheel used as an instrument of torture and execution—where executioners tore flesh from his body in ten different places using red-hot pincers, inflicting maximum pain while keeping him conscious and alive. Following this, his arms and legs were systematically broken with the blunt side of an axe head, shattering the bones in multiple places in a process called "breaking on the wheel." Only after enduring these prolonged torments was Stumpp finally beheaded, and his mutilated corpse was then burned on a pyre. His daughter Beele and mistress Katherine had already been flayed (their skin stripped from their bodies) and strangled before being burned alongside Stumpp's body on the same pyre.

As a warning to the community against similar behavior and as a public demonstration of the terrible fate awaiting those who consorted with the Devil or engaged in similar crimes, local authorities erected a tall pole at the execution site. Upon this pole, they mounted the torture wheel that had been used to break Stumpp's body, topped with a wooden figure of a wolf representing his alleged werewolf form, and at the very pinnacle of this grim monument, they placed Peter Stumpp's severed head. This macabre display remained standing as a permanent reminder of the case and served to reinforce communal anxieties about witchcraft, diabolical transformation, and the necessity of extreme vigilance against supernatural evil.

The case of Peter Stumpp remains deeply troubling to modern historians not because of the werewolf accusations themselves—which no contemporary scholar credits as literally true—but because of what the trial reveals about early modern European justice, the use of torture to extract confessions, the psychology of witch hunts and supernatural panics, and the capacity of communities to inflict horrific violence on their members when gripped by fear of the diabolical and the monstrous. Whether Stumpp committed any actual crimes, whether he was a serial killer whose actions were attributed to supernatural causes, or whether he was an innocent man destroyed by a combination of superstitious belief, judicial torture, and community scapegoating remains impossible to determine with certainty from the available evidence, all of which was produced within the framework of the accusation itself and reflects the assumptions and prejudices of those who believed in the reality of werewolves and diabolical pacts.