Ojáncanu

The Ojáncanu (Cantabrian pronunciation: [oˈhankanu]) is a monstrous cyclops from Cantabrian mythology who represents the embodiment of cruelty, brutality, and destructive natural forces in the folklore of Cantabria, the mountainous region of northern Spain. This fearsome giant serves in Cantabrian traditional narratives as a figure of primal chaos and malevolence, threatening human settlements, disrupting the natural landscape, and embodying the dangerous, untamed aspects of the wilderness that surrounded and sometimes threatened the region's rural communities. The Ojáncanu appears as a towering giant standing between ten and twenty feet tall—far exceeding normal human height and making it a physically overwhelming and terrifying presence.

It possesses superhuman strength that allows it to perform feats impossible for ordinary humans, including uprooting massive rocks, tearing down trees, and destroying structures with ease. Its physical appearance marks it as monstrous and aberrant: most distinctively, it has a single eye in the center of its forehead like the cyclopes of Greek mythology, identifying it as a one-eyed giant in the broader tradition of cyclops legends found across European and Mediterranean cultures. Its hands and feet each contain ten digits rather than the normal five—twice as many fingers and toes as humans possess—giving it enhanced grasping ability and perhaps contributing to its superior strength and climbing capabilities in the mountainous terrain it inhabits.

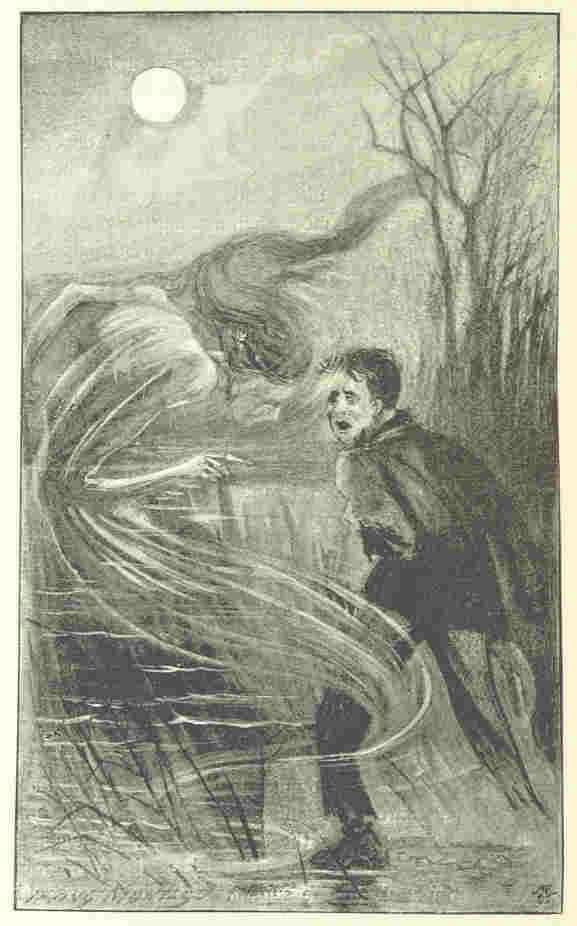

Its mouth contains two complete rows of teeth rather than the single row humans have, suggesting an enhanced capacity for tearing, crushing, and devouring food, and perhaps marking it as particularly savage and predatory. The Ojáncanu's temperament and behavior are described as extremely wild, beast-like, savage, and unpredictable, more resembling a dangerous animal than a rational being despite its humanoid form and giant stature. Physically, it sports a remarkably long mane of distinctive red or reddish hair growing from its head, and equally impressive facial hair including beard and possibly mustache, with both the head hair and facial hair growing to such extraordinary length that they nearly reach all the way to the ground when the giant stands upright.

This abundant hair gives the Ojáncanu a wild, unkempt, and primitive appearance that emphasizes its nature as a creature of wilderness rather than civilization, and the specific detail of red hair may connect it to folkloric associations between red hair and dangerous, supernatural, or demonic beings found in various European traditions. According to Cantabrian folklore, despite the Ojáncanu's overwhelming size, strength, and ferocity, it possesses a specific vulnerability that constitutes a kind of magical weak point or Achilles' heel: apparently the easiest and perhaps only effective way of killing an Ojáncanu is to locate and pull out a single white hair that is hidden somewhere within the tangled mess of its predominantly red beard. This detail creates a fairy-tale logic where the seemingly invincible monster has a secret weakness that clever heroes might exploit, transforming confrontation with the giant from an impossible contest of strength into a challenge of cunning, stealth, and careful observation—the hero must get close enough to the dangerous giant to search its beard, identify the one white hair among presumably thousands of red hairs, and pull it out without being caught and killed in the process.

The female of the species, called an Ojáncana, shares virtually all the physical and behavioral characteristics of the male Ojáncanu including the enormous size, superhuman strength, polydactyly (ten fingers and toes per limb), double rows of teeth, single central eye, wild temperament, and cruel destructive nature. However, the Ojáncana differs from the male in lacking a beard—presumably having smooth faces or at least no significant facial hair—which eliminates the single white hair vulnerability that males possess, potentially making females even more dangerous since they lack this exploitable weakness. Instead, female Ojáncanas are distinguished by possessing extremely long, pendulous breasts that hang down so far that, like their male counterparts' hair and beards, they reach all the way to the ground when the giantess stands normally.

This exaggerated physical feature creates a practical difficulty for the female giants: in order to run—whether chasing prey, fleeing danger, or simply moving quickly—they must lift their enormously long breasts and throw or carry them over and behind their shoulders to prevent them from dragging on the ground and impeding their movement, a detail that adds both grotesque comedy and a kind of monstrous practicality to the legend. Perhaps the strangest and most distinctive aspect of Cantabrian cyclops mythology concerns the reproduction process of these peculiar cyclopean beings, which according to tradition does not involve sexual mating, pregnancy, or birth in any conventional sense. Instead, Ojáncanus and Ojáncanas reproduce through an extraordinary process that combines death, ritual, and spontaneous generation: when an old Ojáncanu dies from age, injury, or having its white beard hair pulled, the surviving members of the cyclops community gather around the corpse and distribute its internal organs among themselves—whether they consume these organs, use them ritually, or distribute them for burial is not specified in most versions of the legend.

After this distribution of the deceased giant's insides, the surviving Ojáncanus bury the corpse beneath an oak tree or a yew tree—both species having deep significance in European mythology and folklore, with oaks associated with strength, endurance, and sacred groves, and yews associated with death, resurrection, and immortality due to their extreme longevity and their poisonous yet medicinal properties. Presumably, from this buried corpse or through some process connected to it, new Ojáncanus eventually emerge or are generated, perpetuating the species without sexual reproduction, though the legend does not specify the exact mechanism or timeline for how new giants arise from the buried dead. The Ojáncanu's behavior and activities consistently embody destructive chaos and malevolent interference with human and natural order.

He is constantly engaged in evil deeds that harm human communities and disrupt the landscape: he tears up massive rocks and boulders from their places, destroying geological stability and possibly blocking paths or creating hazards; he destroys huts, cabins, and other human dwellings, leaving families homeless and vulnerable; he uproots or breaks trees that provide timber, food, and shelter; and he blocks water sources including springs, streams, and wells, depriving humans and animals of essential water and threatening survival. These destructive activities suggest the Ojáncanu represents natural disasters, geological instability, floods, landslides, and other dangerous natural phenomena that threatened Cantabrian mountain communities, personified as deliberate malevolence by a giant monster rather than understood as impersonal natural processes. The Ojáncanu also engages in violent combat with the region's most powerful and dangerous animals, specifically fighting both Cantabrian brown bears—large, powerful predators that historically inhabited the Cantabrian mountains and that would have been among the most dangerous animals that humans in the region might encounter—and Tudanca cattle bulls, a distinctive breed of cattle native to Cantabria known for their strength, aggressive temperament, and formidable horns.

Remarkably, according to the legend, the Ojáncanu always wins these confrontations, defeating even the most powerful natural predators and the most dangerous domestic animals through superior strength, ferocity, or supernatural power, establishing the cyclops as the apex force of destruction in the Cantabrian mountains, more dangerous than any natural animal no matter how formidable. However, despite his overwhelming power and his consistent victories over all natural opponents, the Ojáncanu does have beings that he fears and from whom he will flee or hide: he is terrified of the Anjanas, the good fairies of Cantabrian mythology who represent benevolent supernatural forces, natural beauty, healing, protection, and assistance to humans. The Anjanas are typically described as beautiful, kind, small female fairies who help lost travelers, protect children, assist with household tasks, heal the sick, and generally work to benefit humans and maintain natural harmony.

The fact that the brutal, cruel, destructive Ojáncanu fears these gentle, benevolent beings suggests a moral cosmology in Cantabrian folklore where goodness ultimately holds power over evil, where protective magic can restrain destructive chaos, and where the forces of civilization and order (represented by the helpful Anjanas) can check the forces of wilderness and destruction (embodied by the Ojáncanu), even though in direct physical confrontation the giant would seem far more powerful than the delicate fairies—suggesting that their power over him is moral, magical, or spiritual rather than physical, and that evil, no matter how strong, retreats before genuine goodness and purity. The Ojáncanu legend served multiple functions in traditional Cantabrian society: providing explanations for natural disasters and landscape changes (destroyed trees, displaced rocks, dried springs could all be attributed to the giant's malevolence); warning children and adults about dangers in wild, remote areas where one might become lost, injured, or killed and where blaming a monster was easier than acknowledging random natural hazards; embodying fears of chaos, destruction, and forces beyond human control that constantly threatened fragile mountain communities; and reinforcing moral and social values by showing that even overwhelming evil power has vulnerabilities (the white hair) and will ultimately be checked by goodness (the Anjanas), teaching that cleverness can defeat brute force and that protective virtue provides safety against malevolence, making the terrifying cyclops simultaneously a figure of horror and a creature that can ultimately be overcome or avoided through knowledge, cunning, moral purity, and the protective intervention of benevolent supernatural forces allied with human communities against the destructive wilderness embodied by the one-eyed giant.