Myth of the First Thanksgiving

The myth of the First Thanksgiving is a romanticized and largely inaccurate narrative about a 1621 harvest feast shared by Pilgrims and Indigenous people in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Often called the “Thanksgiving myth,” this version of events has been widely criticized by Indigenous communities and historians for misrepresenting the complex and often violent history between European settlers and Native peoples.

Historian David Silverman summarizes the myth as portraying unidentified, friendly Native Americans who welcomed the Pilgrims, taught them survival skills, shared a meal, and then vanished from history. According to this version, the Pilgrims arrived on the Mayflower in search of religious freedom. While some settlers were indeed Separatists fleeing the Church of England, many others came primarily for economic opportunity.

The myth continues with the signing of the Mayflower Compact, an agreement among male passengers that is often incorrectly cited as the foundation of American democracy and an early influence on the U.S. Constitution. After arriving, the settlers are said to have formed a sincere, peaceful bond with the local Wampanoag, who generously helped them survive the harsh winter out of goodwill.

In reality, the relationship was strategic rather than sentimental. Wampanoag leader Ousamequin initiated contact in March 1621, hoping an alliance with the English would provide political leverage against rival tribes like the Narragansett. Many Wampanoag opposed the alliance, and the settlers also saw the relationship as a means to gain resources.

One of the central figures in the settlers’ survival was Tisquantum—known in legend as Squanto—who acted as a translator and guide. What the myth often omits is that he had been kidnapped by Englishmen in 1614, enslaved in Spain, and only returned to New England in 1619 after learning English. Upon his return, he found his Patuxet village wiped out by disease. The Pilgrims settled on the very land where his village once stood, as it was already cleared.

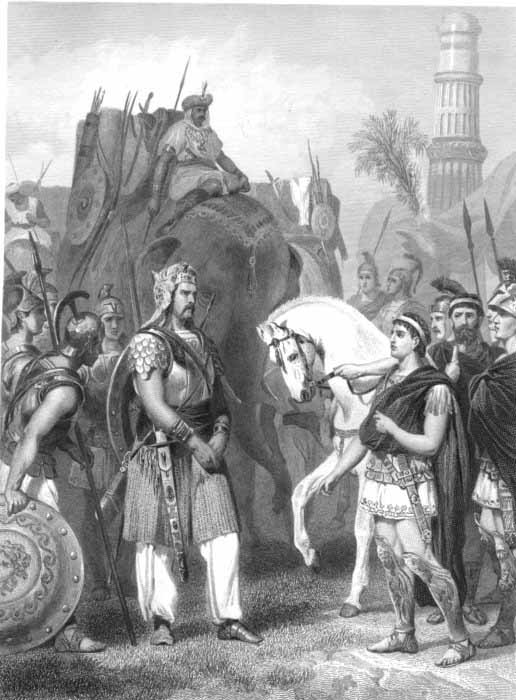

The so-called First Thanksgiving in 1621 is said to have lasted three days and included a feast attended by both Pilgrims and Native Americans. However, historians are unsure whether the Wampanoag were even invited. Some suggest they arrived after hearing celebratory gunfire, believing the settlement might be under attack. Others think their presence was coincidental, possibly due to nearby planting or a diplomatic visit by Massasoit, the Wampanoag leader. In any case, about 90 Wampanoag were present—nearly double the number of English settlers.

There was indeed a shared meal involving food brought by both groups. Primary sources note that the Wampanoag provided five deer, while the settlers contributed fowl and crops they had harvested. The meal likely included cornmeal, pumpkin, succotash, cranberries, and stews made from the venison.

Contrary to popular belief, turkey is not mentioned in any firsthand accounts, and foods like sweet potatoes, pecans, and pies would not have been available. Ingredients like butter, wheat flour, and potatoes were absent, and pie crusts could not be made. Many dishes associated with modern Thanksgiving actually emerged from Southern traditions in the 19th century.

Another common misconception is how the Pilgrims dressed. Popular art often shows them in somber black-and-gray clothing with buckled shoes, but in reality, they wore colorful garments during the week and reserved dark colors for Sunday church services. Buckled shoes were not common at the time.

The Thanksgiving myth also fails to acknowledge the deterioration of relations between settlers and Indigenous people after 1621. The alliance between the Plymouth colonists and the Wampanoag eventually broke down, leading to violent conflicts like the Pequot War in the 1630s and King Philip’s War in the 1670s.

The first documented "day of thanksgiving" in the Plymouth Colony actually took place in 1623, after a drought-ending rain and the return of Captain Miles Standish. Unlike the mythologized 1621 feast, this event is recorded in primary sources as a formal religious observance of gratitude.

In sum, while the 1621 feast did occur and included shared food between English settlers and the Wampanoag, the popular narrative misrepresents the deeper context, motivations, and consequences of the encounter. It simplifies a fraught colonial history into a feel-good story that overlooks the political realities and later tragedies that shaped early American life.