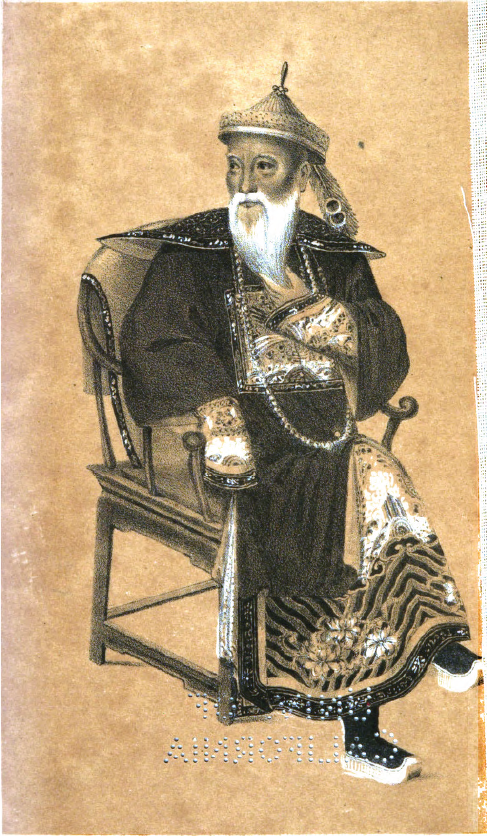

Lin Zexu(林则徐)

Lin Zexu (August 30, 1785 – November 22, 1850), courtesy name Yuanfu, was a Chinese scholar-official, political philosopher, and high-ranking administrator under the Daoguang Emperor of the Qing dynasty who is best remembered for his uncompromising opposition to the British opium trade and his pivotal role in precipitating the First Opium War of 1839–1842. Born in Fuzhou, Fujian Province, Lin rose through the rigorous Confucian examination system to achieve the highest levels of imperial service, holding prestigious positions including Viceroy, Governor-General, and Imperial Commissioner—ranks that demonstrated both his intellectual abilities and the emperor's confidence in his judgment and integrity. Lin's forceful and uncompromising opposition to the opium trade—which British merchants were conducting on a massive scale despite Chinese prohibitions, creating a national public health crisis that was addicting millions of Chinese and draining the empire's silver reserves—served as the primary catalyst that transformed a long-standing commercial and diplomatic dispute into open military conflict in the First Opium War.

By the 1830s, British opium imports from India into China had reached catastrophic levels, creating widespread addiction that devastated families and communities, undermined government authority, corrupted officials who accepted bribes to overlook smuggling, and reversed China's formerly favorable trade balance as vast quantities of silver flowed out of China to pay for the addictive drug. The Qing government had prohibited opium for decades, but enforcement proved ineffective against the combination of British commercial determination, the complicity of corrupt Chinese officials, and the drug's addictive properties that created insatiable demand. In 1838, the Daoguang Emperor, alarmed by the escalating crisis and frustrated by the failure of previous measures, appointed Lin Zexu as Imperial Commissioner with extraordinary powers and sent him to Guangzhou (Canton), the center of foreign trade, with explicit instructions to eradicate the opium traffic once and for all.

Lin approached this mission with the characteristic zeal, moral conviction, and administrative efficiency that had marked his earlier career fighting corruption and opium use in other provinces. Upon arriving in Guangzhou in March 1839, Lin implemented a comprehensive anti-opium campaign that combined moral appeals, legal threats, and coercive force. He demanded that foreign merchants surrender all opium in their possession, promising that legal trade could continue once the illegal drug traffic ended.

When British merchants hesitated, Lin escalated pressure by confining them to their factories (trading compounds), threatening their Chinese employees and business partners with severe punishment if they continued facilitating opium trade, and making clear that he was prepared to use military force if necessary. British Superintendent of Trade Charles Elliot, recognizing that the merchants faced a genuine crisis and hoping to preserve British commercial interests while avoiding bloodshed, eventually instructed British merchants to surrender their opium stocks—over 20,000 chests containing approximately 1,400 tons of opium worth millions of pounds sterling—to Lin's forces. Lin methodically supervised the destruction of this enormous quantity of opium by mixing it with lime and salt and flushing the mixture into the sea over several weeks in June 1839, an operation conducted with elaborate ceremony designed to demonstrate Qing authority and moral righteousness.

This destruction of opium—which British merchants claimed belonged to them as private property and for which they demanded compensation from the British government—became the immediate cause of the First Opium War, as Britain responded to what it characterized as illegal seizure and destruction of British property and violation of free trade principles by dispatching a naval expedition to force China to pay compensation, grant trade concessions, and accept British terms for future commercial relations. Lin's uncompromising stance and his actions in confiscating and destroying British opium are praised by many historians, Chinese nationalists, and anti-drug activists for representing the moral high ground in what they view as a righteous struggle against drug trafficking and imperialist exploitation—Lin was defending Chinese sovereignty, protecting Chinese people from addiction, and upholding Chinese law against foreign criminals who were deliberately poisoning millions for profit. From this perspective, Lin was a principled hero who refused to compromise with evil and who took the only honorable course available to him despite facing overwhelming British military power.

His famous "Letter of Advice to Queen Victoria," in which he appealed to the British monarch's conscience and asked whether she would permit opium to be sold in Britain if it caused the same devastation there, eloquently expressed the moral case against the opium trade and highlighted the hypocrisy of Britain profiting from a drug traffic in China that would never be tolerated in Britain itself. However, Lin is also criticized by some historians for adopting an excessively rigid approach that failed to adequately account for the complex domestic and international realities of the situation. Critics argue that Lin's actions, while morally justified, were diplomatically and strategically naïve: he underestimated British willingness to use military force to defend their commercial interests and uphold what they claimed were violations of international law and property rights; he failed to anticipate that China's military forces, despite numerical superiority, would prove unable to resist modern British naval power and military technology; he did not sufficiently consider that his confrontational approach would unite British commercial interests, British government, and British public opinion behind a war to force China to accept British terms; and he pursued policies that the Qing government's military and economic capabilities could not sustain once Britain responded with force.

From this critical perspective, Lin's inflexible moral stance, while admirable in principle, led to catastrophic practical consequences that a more flexible and diplomatically sophisticated approach might have avoided or mitigated. The First Opium War that resulted from Lin's anti-opium campaign proved disastrous for China. British naval forces, equipped with steam-powered warships, modern artillery, and disciplined troops, easily defeated Qing military forces in a series of coastal battles and river operations, demonstrating China's technological and military inferiority with humiliating clarity.

The war concluded with the Treaty of Nanking in 1842, which imposed harsh terms on China including payment of a massive indemnity (including compensation for the destroyed opium), cession of Hong Kong Island to Britain, opening of five treaty ports to British trade and residence, imposition of fixed low tariffs that eliminated China's control over its own trade policy, and grant of extraterritoriality that exempted British subjects from Chinese law. This "unequal treaty" inaugurated the "century of humiliation" during which China would be progressively carved up by foreign powers exploiting Chinese weakness. The Daoguang Emperor, who had initially endorsed Lin's hardline policies and anti-opium campaign and had encouraged his aggressive actions against British merchants, executed a strategic reversal once the military disaster became apparent and placed all responsibility for the resulting catastrophic war entirely on Lin Zexu.

Lin was dismissed from his position in disgrace in 1840, exiled to remote Xinjiang in western China as punishment for his alleged mishandling of foreign relations and failure to prevent war, and spent years in political wilderness despite his previous distinguished career and his continued conviction that his actions had been morally correct. This scapegoating reflected the Qing court's attempt to deflect blame from the emperor and the dynasty for policies that had proven disastrous, sacrificing a loyal official to protect imperial prestige—a bitter outcome for a man who had acted on explicit imperial instructions and who had genuinely believed he was serving his emperor and country by confronting the opium menace decisively. Despite his fall from power and official disgrace, Lin's efforts against the opium trade and his principled stand against British imperialism have been deeply appreciated and celebrated by subsequent generations of Chinese nationalists, anti-drug campaigners, and those who view the Opium War as a defining moment of imperialist aggression against China.

He has been revered as a culture hero and national symbol in Chinese historical consciousness, particularly after the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, when Communist historiography portrayed him as a heroic patriot who resisted Western imperialism and drug trafficking despite being betrayed by a weak and corrupt Qing government. Lin symbolizes righteous resistance to drug abuse and foreign exploitation in Chinese culture, and his image appears in Chinese textbooks, monuments, museums, and popular culture as an exemplar of integrity, patriotism, and willingness to sacrifice personal interests for the national good. His moral clarity, incorruptibility, and refusal to compromise with what he saw as evil continue to inspire admiration, even among historians who question whether his policies were strategically wise, making Lin Zexu one of modern China's most complex and contested historical figures—simultaneously a moral hero whose principles command respect and a cautionary example of how inflexible righteousness without strategic sophistication can lead to catastrophic unintended consequences.