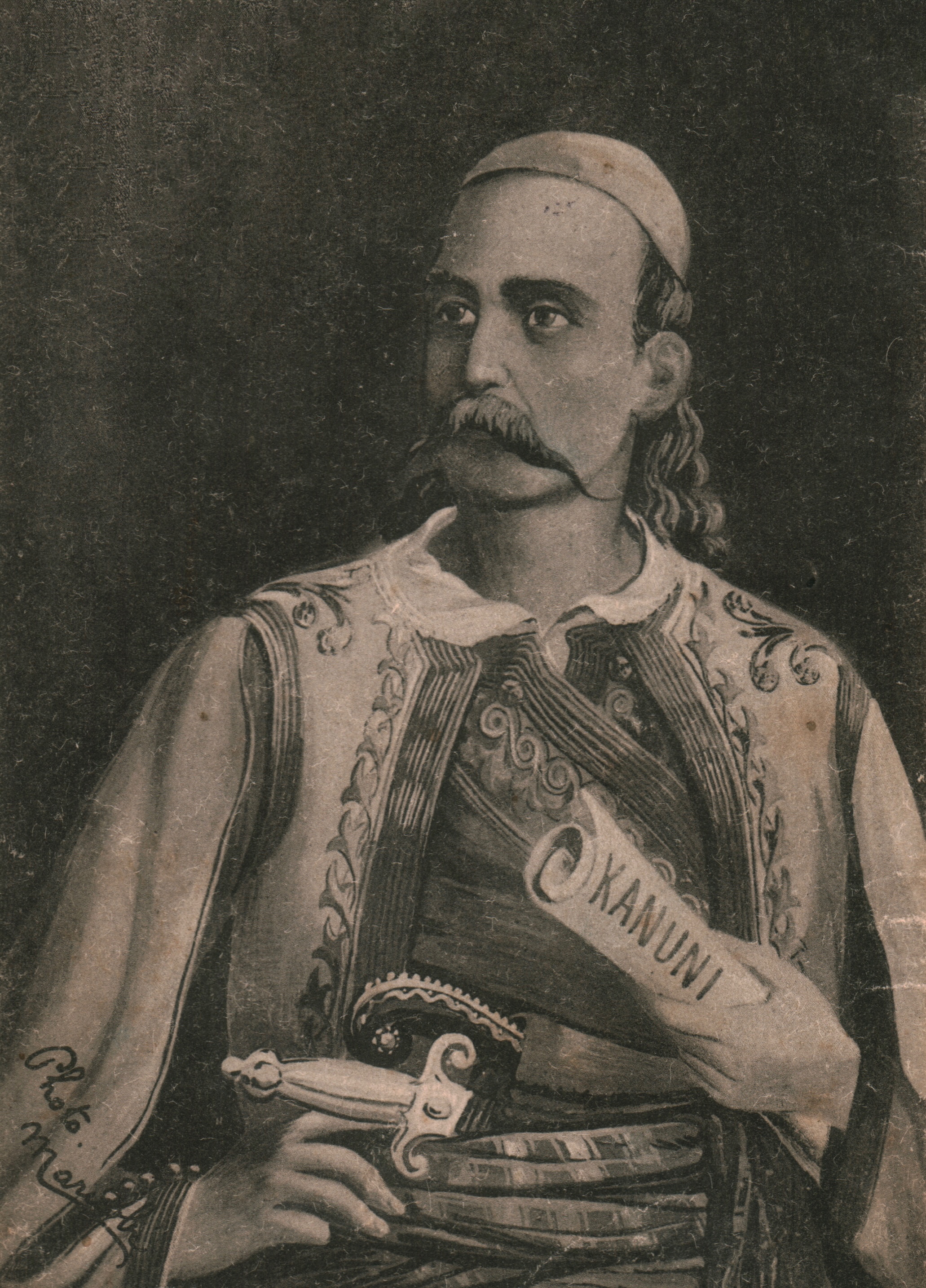

Lekë Dukagjini

Lekë III Dukagjini (1410–1481), commonly known as Lekë Dukagjini, was a fifteenth-century member of the Albanian nobility from the prominent Dukagjini family. A contemporary of Skanderbeg, Dukagjini is best remembered for the Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit, a legal code established among the tribes of northern Albania. He is believed to have been born in Lipjan, Kosovo.

The Dukagjini Principality extended from northern Albania into what is now Kosovo. The western region of Kosovo, sometimes called Rrafshi i Dukagjinit or Dukagjin, derives its name from the Dukagjini family. Until 1444, Dukagjini served as pronoier of Koja Zaharia.

He succeeded his father, Pal II, as ruler of Dukagjini after his father apparently died of apoplexy in 1446. Dukagjini fought under Skanderbeg's command against the Ottoman Empire during the final two years of Skanderbeg's rebellion. He also maintained an intense rivalry with the Albanian nobleman Lekë Zaharia.

The two princes disputed who should marry Irene Dushmani, the only child of Lekë Dushmani, prince of Zadrima. In 1445, Albanian princes gathered for the wedding of Skanderbeg's younger sister Mamica to Muzaka Thopia. When Irene appeared at the celebration, tensions erupted.

Dukagjini asked Irene to marry him, but Zaharia, intoxicated, witnessed this proposal and assaulted Dukagjini. Other princes attempted to intervene, but the conflict escalated, drawing more participants and resulting in several deaths before order was restored. Neither principal combatant suffered physical injury, but Dukagjini felt deeply humiliated.

Two years later, in 1447, Dukagjini ambushed and killed Zaharia in an act of revenge. However, original Venetian documents contradict this timeline, indicating the murder occurred in 1444. According to Venetian chronicler Stefano Magno, it was actually Nicholas Dukagjin, Zaharia's vassal, who killed Lekë Zaharia in battle, not Lekë as the historian Marin Barleti claimed.

Zaharia's death left his principality without an heir, prompting his mother to surrender the fortress to Venetian Albania, the Republic of Venice's coastal possessions. When Skanderbeg unsuccessfully attempted to capture Dagnum in 1447, the Albanian-Venetian War of 1447–1448 began. In March 1451, Lekë Dukagjini and Božidar Dushmani plotted to attack the Venetian-controlled fortress of Drivast.

Their conspiracy was uncovered and Božidar fled into exile. In 1459, Skanderbeg's forces captured the Ottoman fortress of Sati, which Skanderbeg then ceded to Venice to maintain favorable relations with the Signoria before dispatching troops to Italy to support King Ferdinand's efforts to secure his kingdom following the death of King Alfonso V of Aragon. Before the Venetian takeover, Skanderbeg seized Sati and its surrounding territory, expelling Lekë Dukagjini and his forces because Dukagjini opposed Skanderbeg and destroyed Sati before the Venetians could assume control.

Dukagjini continued fighting the Ottoman Empire with limited success, assuming leadership of the League of Lezhë after Skanderbeg's death until 1479. At times his forces allied with the Venetians with papal approval. The Law of Lek Dukagjini (kanun) bears Dukagjini's name because he codified the customary laws of the Albanian highlands.

However, the notion that Gjeçovi's text represents the only authentic version written by Dukagjini himself is incorrect. The Kanun text, frequently disputed and subject to numerous interpretations that evolved considerably since the fifteenth century, was merely named after Dukagjini. While chronicles identify Skanderbeg as the "dragon prince" who fearlessly confronted any enemy, they portray Dukagjini as the "angel prince" who, through dignity and wisdom, safeguarded Albanian identity.

These laws remained in practical use for centuries but were not systematically collected and codified until the late nineteenth century by Shtjefën Gjeçovi. The most notorious provisions of the Kanun regulate blood feuds. Blood feuds resumed in Albania after communism's collapse in the early 1990s, spreading to other Albanian regions and even expatriate communities abroad, having been prohibited throughout Enver Hoxha's regime and contained by relatively closed borders.

Dukagjini's military campaigns against the Ottomans achieved only modest success, and he lacked Skanderbeg's capacity to unify the country and the Albanian people. By the end of the fifteenth century, Albania had fallen completely under Ottoman control.