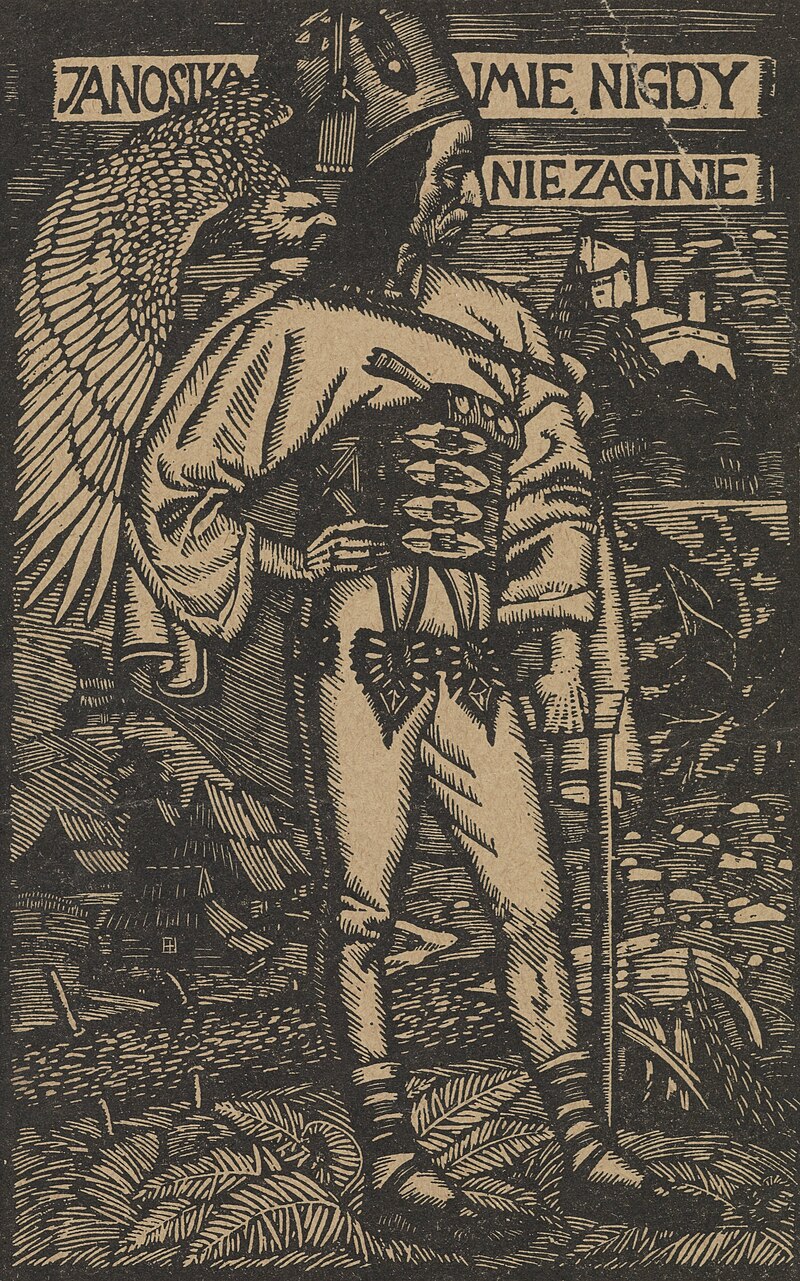

Juraj Jánošík

Juraj Jánošík (first name also rendered as Juro or Jurko; Slovak pronunciation: [ˈjuraj ˈjaːnɔʃiːk]; Hungarian: Jánosik György; baptized January 25, 1688, executed March 17, 1713) was a Slovak highwayman who lived barely twenty-five years but became the central heroic figure of Slovak folklore and national mythology. Jánošík has served as the main character of countless Slovak novels, poems, ballads, and films, evolving from a historical bandit into a legendary folk hero whose story has been told and retold across generations. According to the legend that developed around him, Jánošík robbed wealthy nobles and distributed the stolen wealth to the poor and oppressed—a narrative of redistributive justice often attributed to the famous English outlaw Robin Hood and representing a common archetype in European folklore.

The Jánošík legend is known not only in Slovakia but also in neighboring Poland (where he appears under the name Jerzy Janoszik, also spelled Janosik, Janiczek, or Janicek) and the Czech Republic, demonstrating the transnational appeal of his story across the cultural regions of Central Europe. The actual historical robber Juraj Jánošík bore little resemblance to the romanticized modern legend that grew around his name. The real Jánošík was a member of a bandit group operating in the mountainous border regions between the Kingdom of Hungary and Poland, engaging in highway robbery, cattle theft, and violent crimes for personal gain rather than idealistic redistribution to the poor.

He was captured, tortured, and executed by hanging in 1713 at the young age of twenty-five, ending a criminal career that had lasted only about two years. The content of the legend that subsequently developed partly reflects ubiquitous folk myths found across cultures featuring heroes who take from the rich and give to the poor—narratives that express popular desires for justice and the righting of economic inequalities through the actions of a charismatic outlaw who operates outside unjust legal systems. However, the Jánošík legend was shaped in particularly important ways by activists, writers, and intellectuals during the nineteenth century, when Slovak national consciousness was developing in opposition to Hungarian cultural and political dominance within the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

During this period of national awakening, Jánošík was deliberately transformed into the quintessential highwayman hero in stories that spread throughout the northern counties of the Kingdom of Hungary (territories that correspond largely to present-day Slovakia) and among the Goral inhabitants—the distinctive mountain-dwelling ethnic group of the Podhale region north of the Tatra Mountains. These writers and folklorists collected, embellished, and disseminated Jánošík tales that emphasized his resistance to oppression, his defense of common people against exploitative nobles, and his embodiment of Slovak courage and independence. This constructed legend served important nationalist purposes, providing Slovaks with a heroic figure from their own history who represented resistance to authority and ethnic pride.

The image of Jánošík as a symbol of resistance to oppression and national defiance was significantly reinforced when poems and stories about him became incorporated into the Slovak and Czech middle and high school literature curriculum during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This educational institutionalization ensured that successive generations of young Slovaks and Czechs encountered Jánošík's story as part of their formative cultural education, cementing his status as a national hero whose exploits every educated person was expected to know. The legend received further powerful amplification through numerous films produced throughout the twentieth century that propagated and elaborated his modern legend, reaching mass audiences through the new medium of cinema and creating vivid visual representations of the highwayman hero that shaped popular imagination even more powerfully than written texts.

Jánošík's symbolic significance extended beyond cultural nationalism into active political resistance. During World War II, when Slovakia was nominally independent but effectively a Nazi puppet state, the anti-Nazi Slovak National Uprising of 1944 saw one of the partisan groups fighting against German forces and the collaborationist Slovak regime adopt Jánošík's name. This choice deliberately invoked his legendary status as a fighter against oppression and injustice, connecting the contemporary armed resistance against fascism to the historical tradition of Slovak defiance embodied by the eighteenth-century outlaw.

By claiming Jánošík's legacy, these partisans positioned themselves as continuing his fight for freedom and justice, demonstrating how thoroughly the highwayman's legend had been integrated into Slovak national identity and how effectively his image could be mobilized for political purposes across vastly different historical contexts. Thus, Juraj Jánošík evolved from a minor historical criminal executed in 1713 into one of the most powerful and enduring symbols in Slovak culture—a transformation that illustrates how legends are constructed, how they serve nationalist and political purposes, and how historical figures can be radically reimagined to meet the psychological and ideological needs of later generations seeking heroes who embody their values and aspirations.