Daniel Shays

Daniel Shays (born August 1747, died September 29, 1825) was an American soldier, Revolutionary War veteran, and farmer who became famous—or infamous, depending on one's political perspective—for his alleged leadership role in Shays' Rebellion, a major populist uprising of indebted farmers and rural citizens against controversial debt collection practices, heavy taxation policies, and economic hardship that erupted in Massachusetts between 1786 and 1787. This armed insurrection, which represented the most serious domestic crisis faced by the new United States during the Critical Period between the end of the Revolutionary War and the adoption of the Constitution, profoundly alarmed American political and economic elites and provided crucial impetus for the Constitutional Convention of 1787, as nationalist leaders argued that the weak central government under the Articles of Confederation lacked sufficient power to suppress such popular uprisings and maintain order. However, the actual role that Daniel Shays personally played in the rebellion that bears his name remains significantly disputed among historians and scholars who have examined the documentary evidence.

While contemporary accounts and subsequent historical narratives have traditionally portrayed Shays as the principal leader and organizer of the rebellion—the figure who planned strategy, commanded rebel forces, and made key decisions—more careful historical analysis suggests that this characterization may substantially overstate his importance and that the rebellion was likely a more decentralized, leaderless, or collectively led movement than the "Shays' Rebellion" label implies. Some scholars argue that Shays was merely one among several local leaders and that he was retrospectively elevated to singular leadership status by government officials and contemporary commentators who found it politically and rhetorically useful to personify a diffuse social movement in the figure of a single "rebel leader" who could be demonized, blamed, and held legally accountable. By attributing the rebellion to "Shays" rather than acknowledging it as a widespread popular movement with legitimate grievances, authorities could frame the uprising as the work of a dangerous individual and his deluded followers rather than as evidence of systemic economic injustice and governmental failure that might require fundamental policy reforms.

Shays had served with distinction as a soldier during the American Revolutionary War, participating in several important battles including Bunker Hill, Saratoga, and Stony Point, rising to the rank of captain through demonstrated courage and leadership. Like many Revolutionary War veterans, he returned home to find himself in severe financial difficulty despite his military service. The economic crisis of the 1780s hit Massachusetts farmers particularly hard: agricultural prices collapsed after the war ended, making it difficult for farmers to earn enough from their crops to pay their debts and taxes; the Massachusetts state government, controlled by wealthy eastern commercial interests, imposed heavy taxes payable in hard currency (gold or silver coin) rather than paper money or agricultural produce, which farmers could not obtain; creditors aggressively pursued debt collection through the courts, resulting in thousands of lawsuits and farm foreclosures; and former soldiers like Shays, who had received little or no pay for their military service and who had returned to farms that had deteriorated during their absence, found themselves facing imprisonment for debt, loss of their land, and economic ruin despite having risked their lives to win American independence.

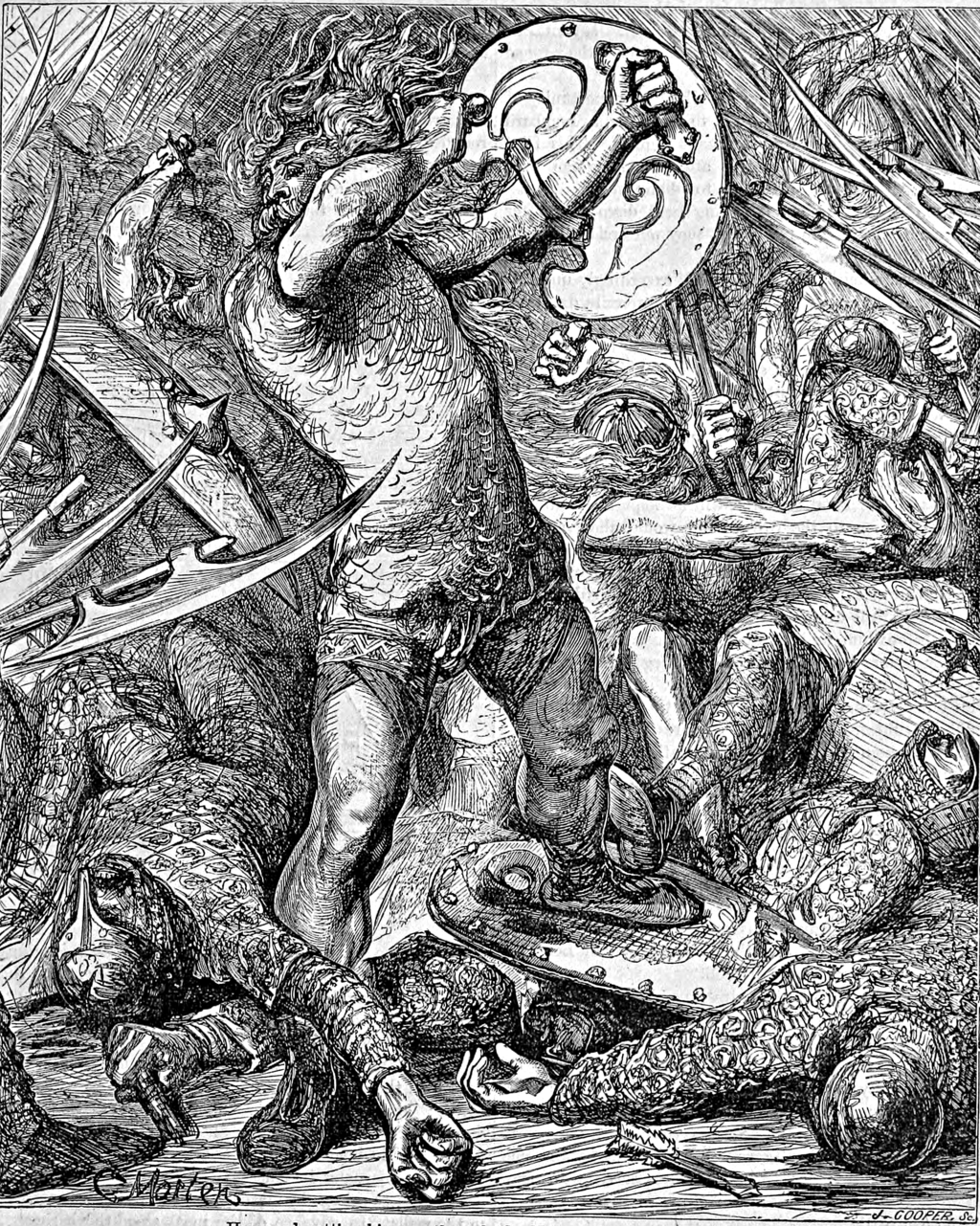

These conditions created widespread anger, frustration, and a sense of betrayal among rural Massachusetts farmers and Revolutionary War veterans, who felt that the government they had fought to establish was now oppressing them through unjust economic policies that favored wealthy creditors, merchants, and speculators at the expense of the ordinary citizens whose military service and sacrifices had made independence possible. Beginning in 1786, armed groups of farmers and veterans began disrupting court sessions throughout western and central Massachusetts, preventing judges from hearing debt collection cases and farm foreclosure proceedings. These "court closings" or "courthouse shutdowns" represented a form of direct action aimed at stopping the legal machinery that was stripping indebted farmers of their property and liberty.

Whether Shays himself initiated these protests, emerged as their leader through demonstrated ability and the respect of fellow rebels, or was simply one participant among many who became associated with the movement through circumstantial prominence remains unclear from surviving evidence. What is documented is that by late 1786 and early 1787, the protests escalated into an armed confrontation when government forces and militia loyal to the state attempted to reopen the courts and suppress the rebellion. An armed encounter occurred at the federal arsenal in Springfield, Massachusetts, in January 1787, where rebel forces (whether under Shays' command or acting independently) attempted to seize weapons and ammunition.

Government artillery fired on the approaching rebels, killing four and scattering the rest, effectively breaking the back of the armed resistance. Following the suppression of the rebellion, Shays fled Massachusetts to avoid arrest and trial for treason and sedition. He eventually settled in Vermont and later New York, living quietly and receiving a federal pension for his Revolutionary War service—an ironic outcome given that he had been branded a dangerous rebel and traitor by the Massachusetts government.

He was eventually pardoned along with other participants in the rebellion as political tensions cooled and authorities recognized that harsh punishment of so many veterans and farmers would be politically unwise and potentially destabilizing. The legacy and historical significance of Shays' Rebellion—and Daniel Shays' association with it—extends far beyond the events themselves. The rebellion terrified American political and economic elites, including George Washington, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and other nationalist leaders, who interpreted the uprising as evidence that the weak central government created by the Articles of Confederation was dangerously inadequate and that popular democracy could descend into mob rule and anarchy if not restrained by a stronger federal government with effective powers of taxation, military force, and law enforcement.

The rebellion thus provided powerful rhetorical ammunition for advocates of constitutional reform and helped create the political momentum that led to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787, where the current United States Constitution was drafted. In this sense, whether or not Daniel Shays personally led the rebellion, "Shays' Rebellion" played a crucial catalytic role in American constitutional history by demonstrating to skeptical Americans that the existing governmental structure was inadequate and that a stronger federal union was necessary—though whether this outcome represented wise statecraft or an elite reaction against legitimate popular grievances remains debated by historians with different political perspectives on early American history.