Chaneque

The Chaneque (also spelled Chanekeh or Ohuican Chaneque, as known to the Aztecs) are legendary beings from Mexican folklore. The name derives from the Náhuatl language, meaning either “those who inhabit dangerous places” or “owners of the house.” These small, sprite-like creatures are believed to be elemental spirits and guardians of nature. Similar beings appear throughout Mesoamerican and Latin American traditions, often called duendes in Spanish. In Yucatec Maya folklore, comparable entities are known as aluxob, spirits that dwell in the forests and fields of the Yucatán Peninsula.

Chaneques are sometimes described as child-sized figures with the faces of elderly men or women. In some stories, they lure people into the wilderness or to the Underworld, where the victims go missing for days and return disoriented, often suffering memory loss. This is said to be because the chaneques temporarily steal their souls, transporting them to Mictlán (the Aztec land of the dead), sometimes through an entrance hidden within a dried kapok tree. If the soul is not retrieved through a ritual, the victim may fall ill or even die.

In other versions of the myth, chaneques frighten intruders so severely that their souls flee their bodies. Traditionally, villagers held specific ceremonies to reunite a person’s soul with their body, recognizing the spiritual danger posed by these encounters.

Throughout Mexican history, chaneques have been depicted both as protectors and as mischief-makers. In colonial-era literature, they were often portrayed more negatively. Mexican writer Artemio de Valle-Arizpe, who studied Mexico’s colonial past while working as a diplomat in Spain and researching at the General Archive of the Indies, wrote several books depicting chaneques as demonic entities.

In his story "Un duende y un perro," set in the late 1500s, a chaneque torments a woman named Doña Luisa, bruising her and inspiring fear, and is described outright as a demon.

Despite these darker portrayals, the myth of the chaneque remains complex and deeply rooted in Mexican culture. In different regions, chaneques take on different roles. In some stories, they are playful, protective, or even helpful—especially toward crops and families who honor them. In others, they are dangerous, disruptive, or sexually threatening.

In rural communities, it was once common for people to leave offerings for the chaneques in return for protection. These offerings were meant to ensure good harvests and ward off evil or unwelcome spirits. Travelers were also advised to wear their clothes inside out when walking through forests as a way to confuse or repel the chaneques.

There are also disturbing tales where chaneques or duendes are believed to abduct young men and women for sexual purposes. Historian Javier Ayala Calderón uncovered a Spanish Inquisition archive from 1676, in which a young man claimed he had sexual encounters with a female duende.

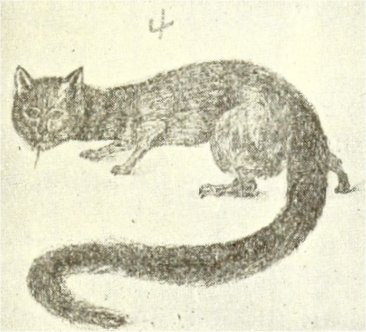

Descriptions of chaneques vary widely depending on the region. Generally, they are said to be small, often naked, and deeply connected to nature, living in forests, rivers, and caves. Some stories emphasize their ability to communicate with animals and protect the jungle, while others depict them as spirits who harm or mislead humans. Though invisible to most adults, children are often believed to be able to see them. Their presence is said to be marked by singing, crying, or shrieking.

One witness, Pedro Cholotio Temo, described a chaneque as a “boy doll or little man who hops and jumps,” wearing a wide-brimmed sombrero and having dark skin. Temo, like others, believed duendes are real and associated with demonic forces, echoing centuries-old Spanish superstitions that connect such creatures to the devil. He also claimed that people who perform satanic rituals are more likely to encounter them.

When angered, chaneques are said to become physically aggressive. In one account, a chaneque shoved a fistful of hay into a prisoner’s mouth, only retreating when the prisoner threatened to start a fire.