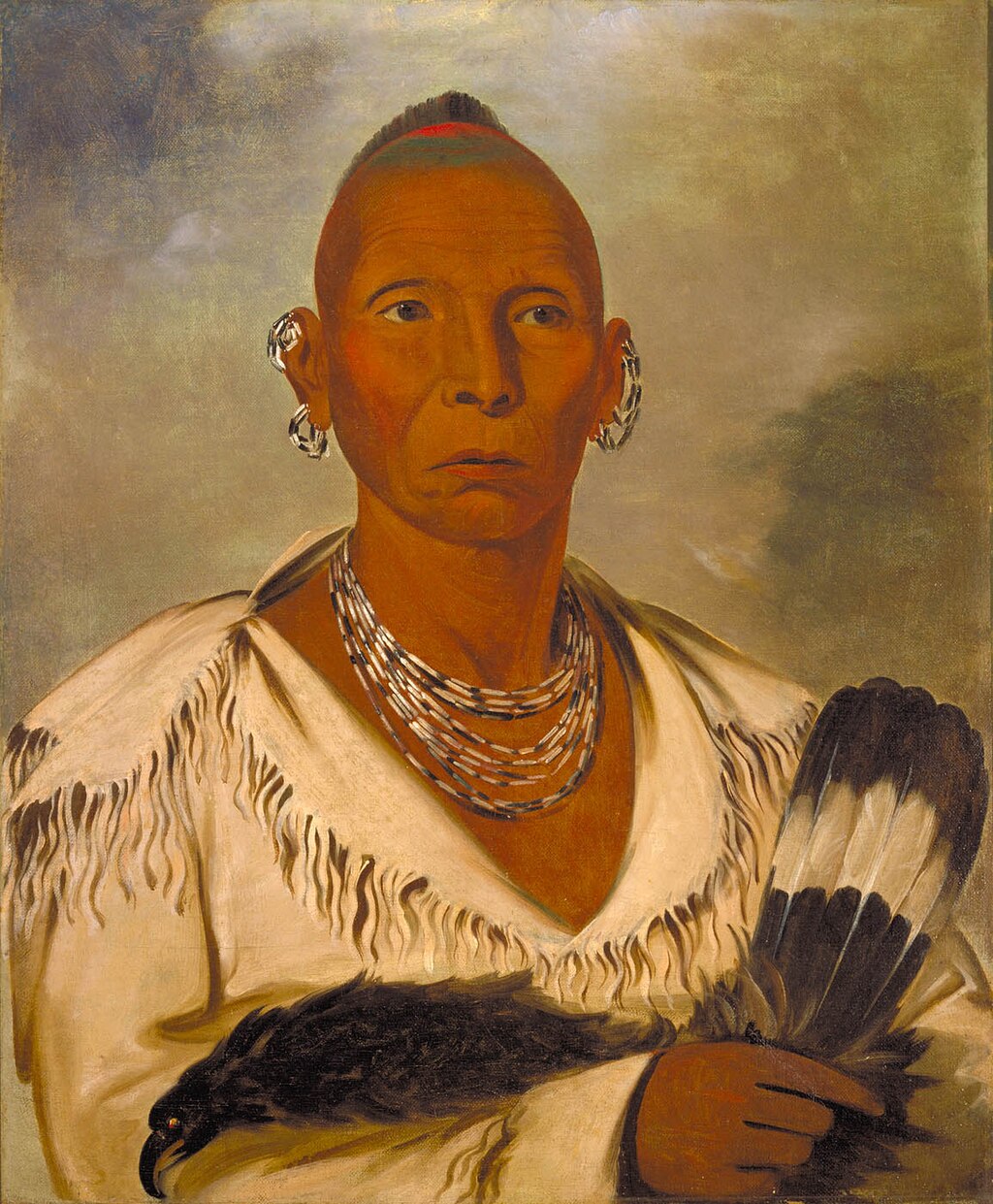

Black Hawk

Mahkatêwe-meshi-kêhkêhkwa, known in English as Black Hawk (born approximately 1767 – died October 3, 1838), was a Sauk leader and warrior who lived in what is now the Midwestern United States and who became one of the most famous Native American figures of the nineteenth century through his resistance to American westward expansion and his subsequently published autobiography. Although he had inherited an important historic sacred bundle from his father—a spiritual object of great religious and political significance in Sauk society—Black Hawk was not a hereditary civil chief who ruled through inherited position within the traditional Sauk political structure. Instead, he earned his status as a war chief or war captain through demonstrated prowess and leadership: by successfully leading raiding and war parties as a young man against traditional enemies including the Osage and other rival tribes, and later by commanding a band of Sauk warriors during the Black Hawk War of 1832, the last major armed Native American resistance east of the Mississippi River.

During the War of 1812, when the United States and Great Britain fought for control of North America and both sides sought Native American allies, Black Hawk and many Sauk warriors fought on the side of the British against the United States in the hope that a British victory would check American territorial expansion and push white American settlers away from Sauk ancestral territory in what is now Illinois, Wisconsin, and Iowa. Black Hawk and other Sauk leaders viewed the British as the lesser threat compared to land-hungry American settlers and the U.S. government's aggressive policy of Indian removal, and they calculated that British support offered their best chance to maintain their lands and traditional way of life.

However, British defeat in the War of 1812 and the subsequent withdrawal of British support left the Sauk vulnerable to intensifying American pressure to cede their lands and relocate west of the Mississippi River. In the years following the War of 1812, disputes over land cessions and treaty interpretation created growing tensions between Sauk communities and American authorities. A controversial 1804 treaty—signed by a small, unauthorized delegation of Sauk representatives in St.

Louis, possibly while intoxicated, and never accepted as legitimate by many Sauk including Black Hawk—purported to cede vast Sauk territories in Illinois to the United States in exchange for annuity payments and the right to continue living on the lands until they were needed for white settlement. As white settlers increasingly encroached on Sauk villages and agricultural lands during the 1820s, most Sauk leadership, recognizing American military superiority and inevitability of removal, reluctantly agreed to relocate across the Mississippi River to Iowa. However, Black Hawk and his followers refused to accept the legitimacy of the 1804 treaty or the necessity of abandoning their ancestral homeland, particularly Saukenuk (located at present-day Rock Island, Illinois), the main Sauk village and burial ground of their ancestors.

In April 1832, Black Hawk led a band of approximately 1,000-1,500 Sauk and Meskwaki (Fox) men, women, and children—collectively known as the "British Band" due to their earlier alliance with Britain—back across the Mississippi River from Iowa into Illinois, attempting to reoccupy their traditional lands and plant crops, possibly hoping that other tribes and British authorities in Canada would support them, and apparently not fully understanding or accepting that their return would be interpreted by Americans as an act of war. Illinois militias and U.S. Army forces under General Henry Atkinson mobilized to force Black Hawk's band back across the Mississippi, but confused initial encounters and an unauthorized militia attack led to the outbreak of the Black Hawk War in May 1832.

What followed was a tragic three-month campaign in which Black Hawk's outnumbered and poorly supplied band, which included many women, children, and elderly people, attempted to evade pursuing American forces while searching desperately for food, allies, and a safe route back across the Mississippi. The war culminated in the brutal Battle of Bad Axe in August 1832, when American forces and their Sioux allies attacked Black Hawk's band as they attempted to cross the Mississippi River to safety, killing approximately 150-300 Sauk men, women, and children in what became essentially a massacre of fleeing refugees. Black Hawk had already left the main group hoping to negotiate surrender terms, but the slaughter proceeded regardless, demonstrating that American forces and frontier militia were determined to inflict maximum punishment on the Sauk regardless of their desperation or attempts to surrender.

After the war ended in catastrophic defeat and the deaths of hundreds of his followers, Black Hawk was captured by U.S. forces along with other leaders including his sons, the prophet White Cloud, and the war leader Neapope. Rather than executing these captured leaders or imprisoning them indefinitely, U.S.

authorities decided they would serve more useful purposes as living demonstrations of American power and magnanimity. Black Hawk and the other prisoners were taken on an extensive tour of several major Eastern cities including Washington D.C., Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, and others, where they were displayed to curious crowds, met with government officials including President Andrew Jackson, and were shown American military installations, factories, and population centers in a deliberate effort to impress upon them the futility of Native American resistance to the United States' overwhelming demographic, economic, and military superiority. Shortly before being released from custody in 1833 and allowed to return west, Black Hawk told his life story to Antoine LeClaire, a mixed-race interpreter who spoke English, French, and several Native languages and who had served as interpreter during various treaty negotiations.

With editorial assistance from John B. Patterson, a newspaper reporter and editor who helped shape the narrative for publication and presumably influenced its style and structure to appeal to white American readers, Black Hawk's account was published as "Autobiography of Ma-Ka-Tai-Me-She-Kia-Kiak, or Black Hawk, Embracing the Traditions of his Nation... in 1833." This book represents the first Native American autobiography to be published in the United States and became an immediate bestseller, going through multiple editions within the first year and remaining continuously in print for decades, indicating strong public interest in Black Hawk's story and in Native American perspectives more generally—though whether readers primarily sympathized with Black Hawk's grievances or simply enjoyed the exotic narrative of a "vanishing race" remains debatable.

The Autobiography presented Black Hawk's own account of his life, the Sauk way of life, the injustices he believed his people had suffered through fraudulent treaties and American aggression, his motivations for the 1832 war, and his ultimate acceptance of defeat and recognition that further resistance was futile. The book combined Black Hawk's personal narrative with ethnographic information about Sauk culture, customs, and traditions, creating a valuable historical document that provided rare direct testimony from a Native American perspective during the period of Indian removal and westward expansion. However, the extent to which the published text accurately represents Black Hawk's actual words and perspectives versus Patterson's editorial interpretations and romantic embellishments designed to appeal to white readers remains a subject of scholarly debate, as with virtually all "as-told-to" narratives filtered through interpreters and editors with their own agendas.

Black Hawk lived his final years quietly under the guardianship of Keokuk, a rival Sauk leader who had cooperated with American authorities and who was rewarded by the U.S. government with recognition as principal chief of the Sauk, though Black Hawk and many traditional Sauk questioned Keokuk's legitimacy and viewed him as a collaborator who had sold out his people's interests. Black Hawk died on October 3, 1838, at age seventy or seventy-one, in what is now southeastern Iowa, near the Des Moines River.

Even in death, indignities continued: his remains were stolen from his grave by a doctor who displayed the skeleton as a curiosity until it was destroyed in a fire, reflecting the exploitation and disrespect Native American remains suffered throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Despite—or perhaps partly because of—his military defeat and the tragic end of his resistance movement, Black Hawk has been honored with an enduring and extensive legacy that far exceeds that of most Native American leaders of his era. His autobiography remains in print and widely read, studied in American literature and history courses as an important primary source on Native American perspectives during the removal era.

His name has been commemorated through numerous eponyms including cities (such as Black Hawk, Colorado), counties, parks, sports teams (most notably the Chicago Blackhawks hockey franchise, whose use of his name and image remains controversial), schools, and various other institutions and geographical features throughout the Midwest. Statues and monuments honor his memory in Iowa, Illinois, and elsewhere. This legacy reflects complex and often contradictory American attitudes toward Native American resistance: on one hand, admiration for Black Hawk's courage, dignity, and principled stand in defense of his homeland and people; on the other hand, romanticization of a "noble savage" who conveniently represents a safely defeated and vanished past rather than ongoing Native American struggles and grievances that might require contemporary Americans to reckon with continuing consequences of conquest and dispossession that Black Hawk's story exemplifies.