Betsy Ross

Elizabeth Griscom Ross (née Griscom; January 1, 1752 – January 30, 1836), also known by her second and third married names Ashburn and Claypoole following the deaths of her first two husbands, was an American upholsterer and seamstress who became one of the most famous figures in American patriotic mythology after her relatives claimed in 1870—nearly a century after the alleged events and thirty-four years after her death—that she had designed and sewn the first United States flag, commonly known as the Betsy Ross flag with its distinctive circle of thirteen five-pointed stars representing the original thirteen colonies. According to the story promoted by Ross family tradition, General George Washington, commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, along with two members of a congressional committee—the wealthy merchant and financier Robert Morris and Colonel George Ross (who was Elizabeth's deceased first husband's uncle)—visited Elizabeth Ross at her upholstery shop in Philadelphia in 1776. During this meeting, Washington supposedly showed Ross a sketch of a proposed flag design featuring six-pointed stars.

Ross, demonstrating her practical seamstress expertise, convinced Washington to change the stars' shape from six-pointed to five-pointed by taking a piece of fabric, folding it efficiently, and making a single strategic cut that produced a perfect five-pointed star, thereby demonstrating that this design was both easier and speedier to execute in production—a persuasive argument that combined aesthetic appeal with manufacturing efficiency that would be important if flags were to be produced in quantity. However, professional historians have consistently dismissed this story from its first appearance in the 1870s through the present day, noting the complete absence of archival evidence, contemporary documentation, or other recorded verbal tradition to substantiate any aspect of this narrative about the creation of the first United States flag. The story appears to have first surfaced publicly in the writings of Ross's grandson, William J.

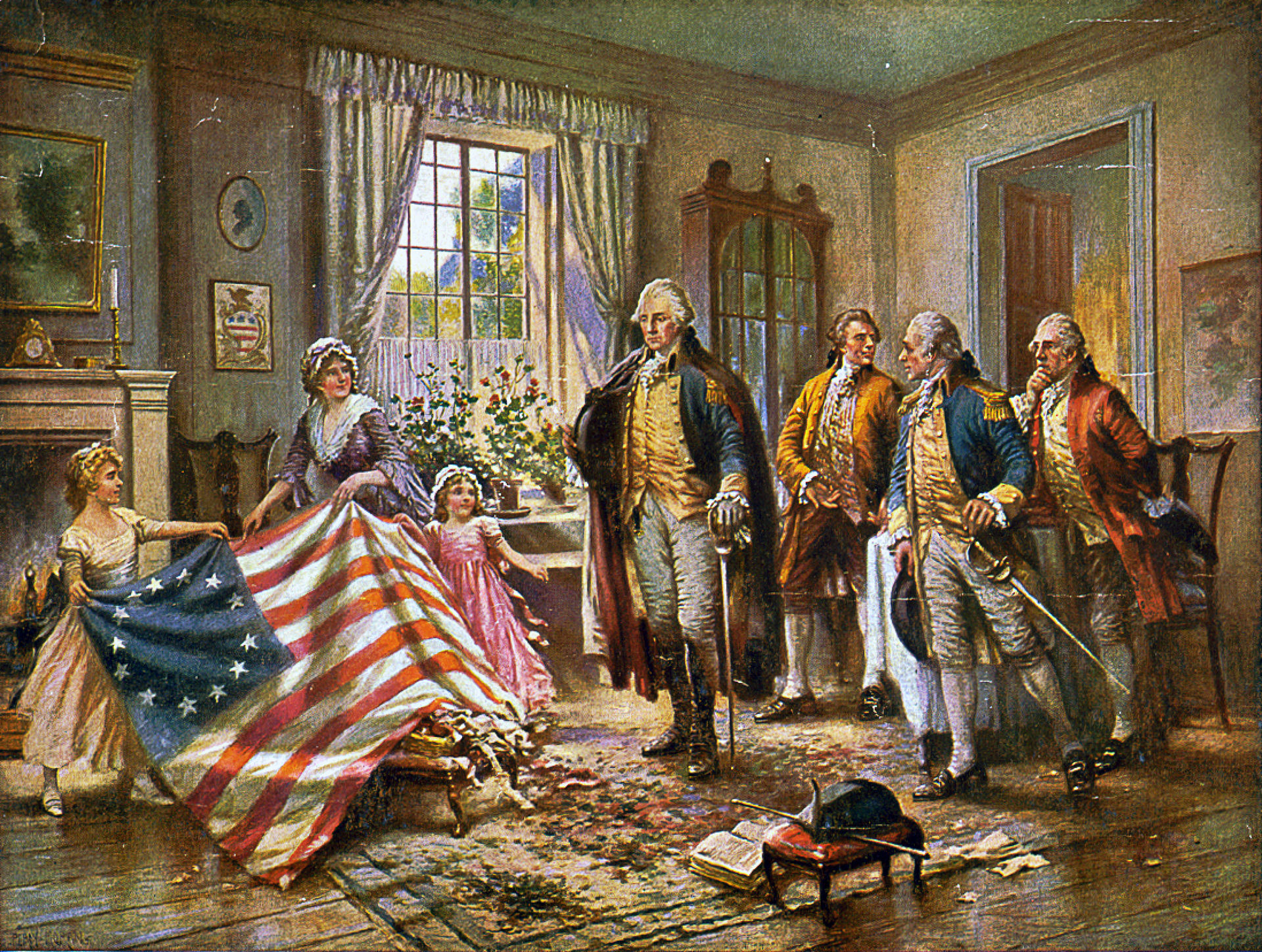

Canby, in the 1870s—a full century after the events supposedly occurred—with no mention or documentation of this dramatic episode appearing in any earlier records, newspapers, family letters, or other sources from the Revolutionary period or the first decades of the nineteenth century when Elizabeth Ross herself was still alive and could have confirmed or denied the story. This complete documentary silence during the lifetimes of all the principals is highly suspicious and strongly suggests the story was a later invention or embellishment rather than a forgotten historical fact being recovered. The Betsy Ross myth gained significant cultural momentum and visual power when it was incorporated into a large, dramatic oil painting created by artist Charles H.

Weisgerber that appeared at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where millions of fairgoers saw this artistic representation of the patriotic legend. The painting depicted the supposed 1776 meeting with Washington, Morris, and Ross examining the flag in Ross's shop, creating a vivid and emotionally appealing image that lodged in American popular consciousness despite its fictional basis. Weisgerber subsequently became an active promoter of the Betsy Ross myth, even purchasing a house in Philadelphia that he deemed and marketed as "The Betsy Ross House," claiming it was the location where the first flag had been sewn (though historical evidence for this identification was also lacking).

Weisgerber solicited money from patriotic Americans nationwide for the maintenance and operation of this house as a tourist attraction, and with these fundraising appeals, he provided a synopsis of the Betsy Ross story along with reproductions of his painting, effectively using his art to generate and sustain a mythological narrative that served commercial purposes while becoming embedded in American patriotic culture and elementary school history lessons. While the story of Ross creating the first United States flag is almost certainly false, what is historically documented is that Ross did make flags professionally for the Pennsylvania Navy during the American Revolution, establishing her as a legitimate participant in the revolutionary cause even if her specific contribution was far less dramatic and symbolically significant than the myth suggests. After the Revolution concluded, she continued her flagmaking business for over fifty years, producing United States flags for various government and private customers, including a documented commission in 1811 to create fifty large garrison flags for the United States Arsenal located on the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia.

This long career in flagmaking provided the kernel of truth around which the mythological narrative could be constructed—Ross genuinely was a flagmaker during the relevant period, making the false story of her creating the first flag seem plausible enough to gain traction. The flags of the Pennsylvania navy were overseen administratively by the Pennsylvania Navy Board, which reported to the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly's Committee of Safety, the revolutionary government body responsible for military preparedness and defense. In July 1775, during the crucial early period of organizing colonial resistance, the president of the Committee of Safety was Benjamin Franklin, and its membership included both Robert Morris and George Ross—the same two men who later legend claimed accompanied Washington to Ross's shop.

At that time, the committee ordered the construction of gunboats and other naval vessels that would eventually require flags as part of their standard equipment. However, as late as October 1776, well after the supposed June 1776 flag design meeting with Ross, Captain William Richards was still writing to the Committee of Safety requesting information about what flag design he should use when ordering flags for the Pennsylvania fleet—a fact that contradicts the notion that the flag design had been settled months earlier through Ross's meeting with Washington. Nevertheless, Ross was definitely among the seamstresses and flag makers hired to produce flags for the Pennsylvania naval fleet.

An entry dated May 29, 1777, in the official records of the Pennsylvania Navy Board includes a documented payment order compensating her for completed work, worded as follows: "An order on William Webb to Elizabeth Ross for fourteen pounds twelve shillings and two pence for Making Ships Colours [etc.] put into William Richards store……………………………………….£14.12.2." This archival record provides concrete evidence that Ross was producing naval flags by 1777, though it says nothing about her designing the United States flag or meeting with George Washington. The Pennsylvania navy's ship colors that Ross and other contractors produced included several distinct flags serving different functions according to naval tradition and signaling requirements. The ensign was a blue flag with thirteen stripes—seven red stripes alternating with six white stripes—arranged in the flag's canton (the upper-left-hand corner), representing the thirteen colonies united in resistance to British rule.

This ensign was flown from a pole (the ensign staff) at the rear (stern) of the ship, identifying the vessel's national or state allegiance. The long pennant measured considerable length and featured thirteen vertical red-and-white stripes near the mast end where it attached, with the remainder of its length being solid red as it tapered to a point. This streamer flew from the top of the ship's mainmast—the tallest central pole that held the largest sails—and served both decorative and identification purposes.

The short pennant was entirely solid red and flew from the top of the ship's mizzenmast—the pole holding sails nearest the stern (rear) of the ship—completing the vessel's complement of flags and pennants that announced its identity, improved its visibility, and contributed to the pageantry of naval warfare and diplomacy. Thus, while Betsy Ross has achieved immortality in American popular culture and patriotic mythology as the creator of the first American flag—her image appearing in countless illustrations, her story taught to generations of schoolchildren, and her supposed house remaining a popular Philadelphia tourist destination—the historical evidence demonstrates that this fame rests on a legend created a century after the supposed events, promoted through art and commercial tourism, and lacking any contemporaneous documentation. The real Elizabeth Ross was a hardworking craftsperson who supported herself and her family through upholstery and flagmaking during and after the Revolution, contributing to the American cause in practical if undramatic ways, but almost certainly not through the symbolic act of creating the first Stars and Stripes that legend attributes to her.

Her story thus exemplifies how patriotic myths can eclipse historical reality when nations seek founding narratives that personalize abstract political developments, provide emotionally satisfying origin stories for national symbols, and offer heroes—particularly female heroes in narratives traditionally dominated by male military and political figures—whom citizens can admire and with whom they can identify, regardless of whether the stories accurately represent historical events.