Ammit

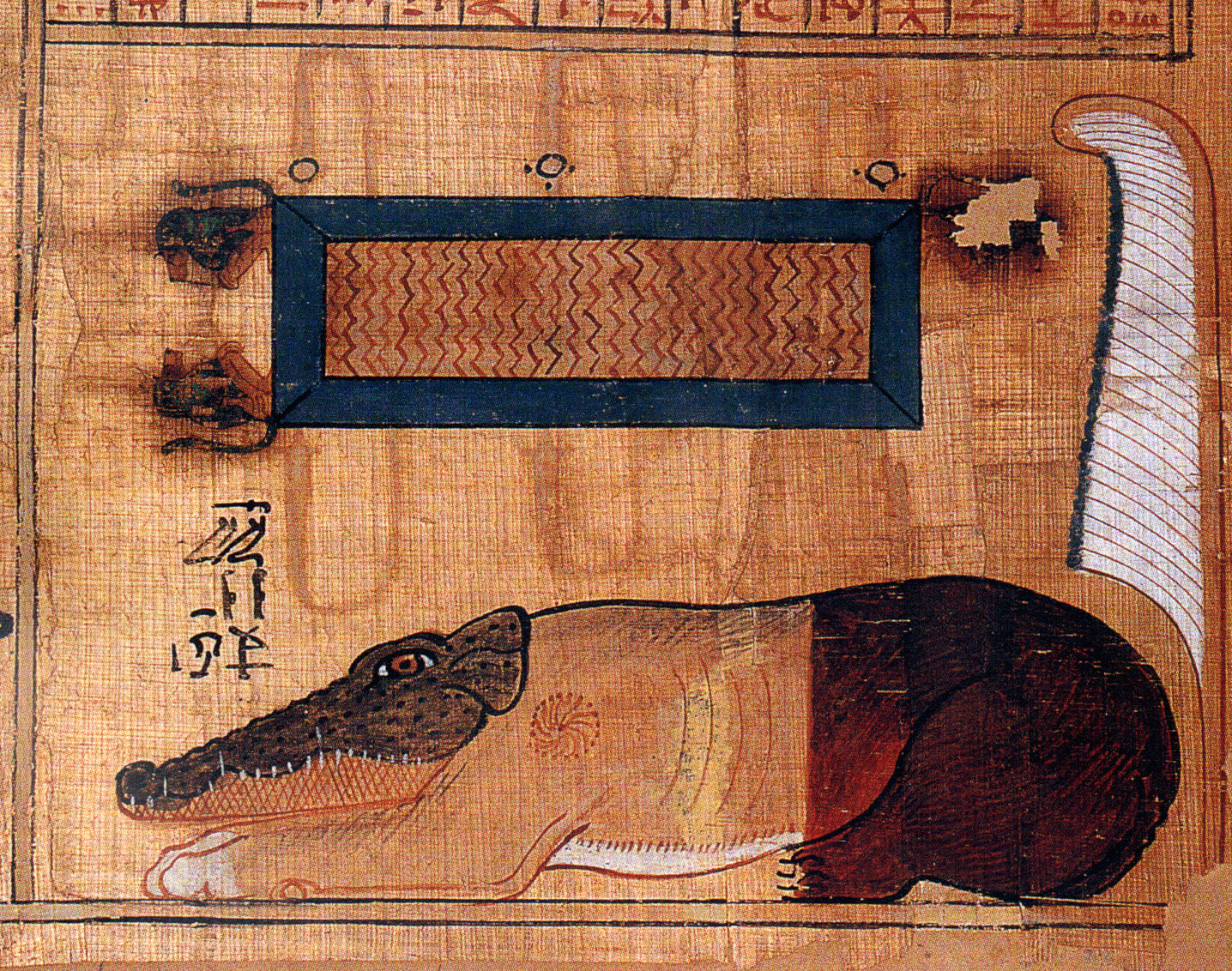

Ammit (pronunciation: /ˈæmɪt/; Ancient Egyptian: ꜥm-mwt, meaning "Devourer of the Dead"; also rendered in various sources as Ammut or Ahemait) was an ancient Egyptian supernatural entity whose precise theological classification remains somewhat ambiguous—sometimes described as a goddess, sometimes as a demon or chimeric being—characterized by a terrifying composite form combining the forequarters of a lion, the hindquarters of a hippopotamus, and the head of a crocodile. This nightmarish assemblage deliberately incorporated the three largest and most dangerous "man-eating" animals known to the ancient Egyptians, creatures that represented the most feared predators in their environment: the lion from the desert margins, the hippopotamus from the Nile River (which despite its herbivorous diet was extraordinarily aggressive and responsible for numerous human deaths), and the crocodile from the same waters, creating a monster that embodied multiple dimensions of lethal threat. In ancient Egyptian religion and funerary beliefs, Ammit played a crucial and fearsome role during the judgment of the dead, one of the most significant moments in the complex funerary ritual that determined the fate of the deceased's soul in the afterlife.

According to the religious texts and iconography preserved in the Book of the Dead and tomb paintings, when a person died and their soul traveled to the Hall of Two Truths in the underworld realm of Duat, they underwent a solemn judgment presided over by Osiris, the god of the dead and resurrection, with the jackal-headed god Anubis conducting the weighing ceremony and the ibis-headed Thoth recording the results. During this judgment, the deceased's heart—believed to be the seat of emotion, memory, intelligence, and moral character rather than merely a physical organ—was placed on one side of a great balance scale, while on the other side sat the feather of Ma'at, representing truth, justice, cosmic order, and righteousness. If the deceased had led a virtuous life in accordance with Ma'at, speaking truth, treating others justly, and following proper religious and ethical conduct, their heart would balance perfectly against or weigh less than the feather, demonstrating their worthiness to proceed into the blessed afterlife of the Field of Reeds, an idealized eternal paradise.

However, if the heart was heavy with sin, wickedness, lies, cruelty, or violations of Ma'at—weighed down by the misdeeds and moral failings accumulated during earthly life—it would tip the scales against the deceased. At this catastrophic moment of failed judgment, Ammit, who lurked beside the scales throughout the weighing ceremony, would immediately devour the condemned heart and often the entire soul or spiritual essence of the failed deceased. This consumption by Ammit represented the "second death"—a complete and permanent annihilation of the individual's existence, more terrible than physical death because it meant the utter destruction of the soul with no possibility of resurrection, rebirth, or continued existence in any form, consigning the wicked to absolute non-being rather than punishment or alternative afterlife.

The ancient Egyptians, who invested enormous cultural energy and resources into ensuring survival after death through mummification, tomb construction, funerary texts, and offerings, regarded this ultimate obliteration as the most horrifying fate imaginable, making Ammit a figure of profound dread whose very presence during judgment ensured that the deceased would truthfully recite the Negative Confession (the declaration of sins not committed) rather than risk her terrible appetite through lies or false claims of righteousness.